Aboriginal spirituality and Christianity have much in common, but Uncle Vince Ross thinks there are a few things Christians could learn from the First Peoples to make their faith more holistic.

By David Southwell

Even though it wasn’t until the age of 12 that Uncle Vince Ross seriously encountered Christianity he says its essence was already very familiar to him.

That is because from a young age his Aboriginal grandparents and aunties imbued a spiritual awareness and understanding of beliefs that long predate Christianity – an awareness and understanding Vince believes complements rather than contradicts the teachings of the Bible.

Vince had no Sunday schooling or even any regular schooling until age 11 because his father, a bridge repair worker, continually moved the family throughout Victoria and southern NSW looking for work.

During this nomadic childhood Vince grew up on riverbanks, sheltered by humpies (temporary structures made out of bush materials) or lean-tos and generally ran wild in a matter that would make Huckleberry Finn jealous.

“We had a fabulous time, going rabbiting or hunting or fishing for the day, while those poor other kids had to go to school,” Vince says.

“When finally I had to go to school it was like the end of the world. I thought ‘it doesn’t get any worse than this, does it?’”

To consign Vince to his schooling fate, his dad took a more permanent job in Deniliquin and this led to an encounter with the Salvos, who were the only church group prepared to venture into the Aboriginal reserve outside town.

“The attitude in Deniliquin at the time was ‘Oh, these black fellas, you can’t do anything for them’,” Vince says.

“When the Salvos come to us they didn’t bring songbooks and Bibles, they brought food, hammers and nails and helped us build little humpies on the riverbank; practical things.

“So, this is my first encounter with Christianity, as such, at the age of 12. Up until that time I knew nothing about God because I just didn’t understand what they were talking about at the Catholic school. Most of it was in Latin anyhow.”

Vince realised the message from the Salvos reflected what he had learnt from his Aboriginal family.

“When our old people were talking in this spiritual sort of language, for people who had never been to church or had any of that sort of influence, they were talking the same thing that the Salvos were talking about,” Vince says.

As an example, he points to striking similarities between First Peoples’ beliefs and the Genesis story of creation.

“Most Aboriginal people talk about there was a time there was nothing, like a darkness, they talk about that,” Vince says.

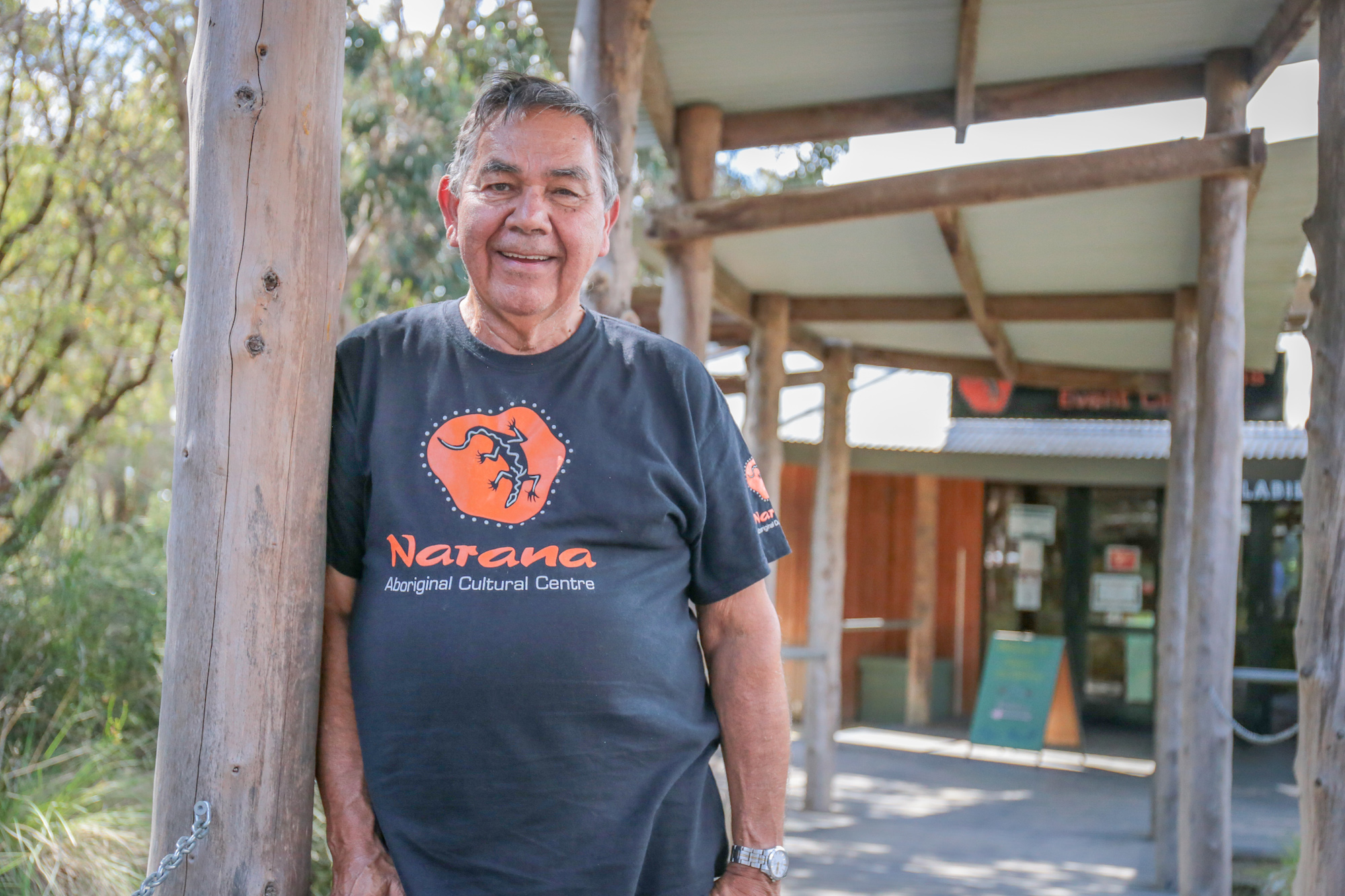

“If we listen to each other, we can create whatever we want” – Uncle Vince Ross. Photo: Mikaela Turner

“Whenever I’m asked about my spirituality versus Christianity my reply is simply I have no problem with that because we are talking about the same thing.”

It’s a view that hasn’t historically been reciprocated by the Church.

For example, early influential Presbyterian missionary John Dunmore Lang wrote that Aborigines had “nothing whatever of the character of religion or of religious observance, to distinguish them from the beasts that perish”.

Vince said the Aboriginal spirituality that the missionaries were oblivious to, or dismissive of, was directed to a creator spirit that the colonialists knew by another name.

“We were calling God ‘Bunjal’ the creator spirit,” Vince says.

“Creation was a demonstration allowing us to understand the spirit world – if we see the eagle flying over there’s a sense Bunjal’s watching over us.

“I know that God is worshipping spirit in truth and our mob have practiced that for a long time and continue to do so today.

“As an Elder said, we have known about the father for a long time, now we are learning about the son, Jesus.

“I’ve never assimilated or thought I had assimilated, but I have adapted. Nowhere did I see that Aboriginal stuff needs to be pushed aside. I saw that as part of the Christian faith.”

Vince said a great opportunity was missed by the invading colonialists.

“The missionaries thought when they came they’ve got to convert all these heathens because what they are talking about it’s not the Biblical way,” he says.

“I think they got that wrong. If they had have sat with the people and tried to understand what was the spiritual journey that these people have been on for thousands of years they would have found out something different.”

Vince believes that western Christianity has widely adopted a mindset which tends to separate the creator and creation, the spiritual and the scientific, leading to a faith that is not holistic.

This leads to an abstract sense of God in being in his heaven watching down, mostly as a spectator, after setting the wheels in motion.

This God-high-above only gets the skywards attention of his followers at designated prayer times or in church.

“I think the Christian mainstream has got it wrong, in that you go to church on Sunday morning and pick up a bit of spiritual for the week,” Vince says.

“That doesn’t happen with Aboriginal people because spiritual is what you do all the time, you are in that position, the mode or area, where things are always happening around you.

“It’s not just about whether we are there Sunday morning with our suit and tie on. It’s every day, what are the things we do in community that connect us.”

Vince says when First Peoples’ get together it’s not about denominations. “We’re all part of God’s family and we’re all in it together.”

Vince says First Peoples’ beliefs differ a little from region to region, but he finds surprising commonality when he talks to those even from far distant communities.

“We’d be on the same track. They may have painted the building a little different colour, but it’s the same building,” he says.

“You couldn’t tell the difference in our speech – we would be talking about the same thing, talking about that of the heart and that of understanding creation, but we were using all these different examples.

“Whenever Aboriginal people get together, many of them from different denominations, we never represent that denomination in the sense ‘I’ve got my tag on here, I’m from the Salvation Army’.

“No, we say ‘I’m from God’s family and I am with you and we’re all part of God’s family and we’re all in it together’.”

First Peoples’ beliefs and culture are not always well understood, or indeed that easy to understand, from a European perspective.

For example, the Dreamtime could perhaps more accurately be called the Dreaming in the same sense of a church that is “Uniting”.

It is not a one-off event or period, but a timeless process where place and people are shaped by, interact with, and reflect the spiritual world. This ties into a vital aspect of Indigenous belief, which Vince says is sometimes wrongly characterised, the inseparable spiritual link to country.

“We’re not worshipping the land,” Vince says.

“We’ve never gone around worshipping the trees or the land, but we’ve recognised the connection with it. It’s actually respecting Banjul’s creation.

“A little example of that was that we had a school going through the Narana Centre garden and there was a limb coming down and a little fella broke the limb off.

“I just touched him on the shoulder and said ‘mate, that tree was alive, but that tree couldn’t say to you ‘don’t break my limb’.”

Vince says other aspects of First Peoples culture are also widely misunderstood, such as corrobees.

“Corroboree wasn’t just dance, a Saturday night shoe-shuffle, but it was a ceremony like you might go to church. It might be a wedding, it might be a baptism, whatever. It’s a time of celebration.”

Walkabout is another practice with a deep spiritual significance.

“With walkabout, people think it’s just taking time out – that you’re dodging the real issues of the day,” Vince says.

“For us, walkabout was a time of refreshment and spiritual nourishment of stopping and resting. We allow the spiritual side of what we are talking about to come into that space, that understanding of the great creator God.”

Vince was inspired to work for the UCA by Indigenous leaders such as Rev Charles Harris.

“They spoke very loud and strong about us being God’s creation and that in our spirituality, our lives, what we’re on about and how we want to operate in a Christian way, there’s no conflict here,” Vince says.

“It was about us being holistic in our approach to life and ministry. If I reflect back on my life with my old grandparents and folks on the riverbanks, it’s stuff they were talking about. It’s connecting up with what the Uniting Church was talking about.

“I just wish that there were more people who could come across and see what Aboriginal people are talking about and express that which is of the spirit, because we all are spiritual.”

In 2010, the Uniting Church adopted a Preamble to its Constitution which states:

“The First Peoples had already encountered the Creator God before the arrival of the colonisers; the Spirit was already in the land revealing God to the people through law, custom and ceremony.”

While some Christian groups still tell First Peoples to leave their culture and beliefs “at the door”, Vince believes those attitudes are changing.

His commitment to fostering a greater understanding and awareness of how First and Second Peoples can build things together led him to establishing the Narana Aboriginal Cultural Centre, which sits on the Surf Coast Highway just outside of Geelong.

The centre, run by the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress, aims to immerse visitors into First Peoples’ culture.

The wooden shed-like buildings sit in five acres of recultivated bushland, home to emus, wallabies and kangaroos.

“Narana means listening, hearing and understanding. If we listen to each other we can create whatever we want,” Vince says.

“This place is about changing attitudes of the wider community. We have people who come here and say ‘there’s something different’, there’s a real spirit in the place.

“We’re building understanding and better relationships and more trust and more respect.

“We sit together and have a yarn, we talk to each other and we have got to do more of that because I don’t think there’s anyone who’s got it all worked out.”