The Church as a Prophetic Voice in Australian Society: Past, Present, Future

By Rev Alistair Macrae

The language of “public theology” is a tautology. Theology, at least in the Uniting Church’s account of it, is inherently public. According to the Uniting Church’s Basis of Union, God’s big project is the renewal of the whole creation, not only individual souls. To regard Christian faith as something merely therapeutic or personal diminishes its purpose. The church is called to speak and act for the common good, contesting injustice and embodying hope.

Prophetic roots

The prophetic vocation of the church has deep biblical foundations. The Hebrew prophets insisted that the health of a society is measured by its treatment of the poor, and that worship which neglects justice is false religion. Jesus drew directly on this tradition, announcing his mission in the words of the prophet Isaiah: “to proclaim good news to the poor, release to captives, sight to the blind and freedom for the oppressed”.

The three traditions that formed the Uniting Church carried strong commitments to justice, community care and prophetic ministry.

Church union and the Statement to the Nation

The Statement to the Nation (1977) set out the UCA’s early vision: to oppose poverty, racism, and discrimination, and to work for justice, peace and care for creation. Yet the statement failed to acknowledge First Peoples — a silence belatedly addressed through the Covenant with the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress, the Apology and the Revised Preamble to the Constitution.

The 2009 Assembly’s adoption of the Revised Preamble was a landmark. It named the truth of colonisation and confessed the church’s complicity in the process of dispossession and oppression. At the end of that Assembly debate, when Congress members blessed the Assembly with gum leaves in a Spirit-filled act of grace, the church experienced prophetic truth-telling at its best. Yet it must be acknowledged that incorporation of these commitments into church life remains uneven.

Present challenges

Over recent decades, the church’s social justice capacity in Assembly and Synods has diminished, with research and advocacy roles reduced or, in some Synods, devolved to agencies. While UnitingCare agencies continue to provide research, advocacy, and policy engagement, church leaders themselves are less visible in public debate. Risk aversion and declining confidence in the Gospel’s transformative power have muted our prophetic voice. Revelations of abuse within church institutions and acknowledgement of complicity in colonialism have eroded public trust. The church must reckon honestly with these failures while continuing to resist injustice.

We must “work to prioritise voices and perspectives from the social margins”, writes Rev Alistair Macrae.

Social justice today and tomorrow

The UCA’s numerical decline should not silence us. Instead, we are called to speak with confident humility — neither triumphalist nor timid, but faithfully pointing to the reign of God and its distinctive values. The early church was socially marginal, yet celebrated hope and proclaimed the risen Lord with joy.

The church’s witness must be grounded in living in the way and the company of Jesus Christ: living justly, forgiving, resisting evil, while also nurturing spiritual life through prayer and worship. Without the spiritual dimension, activism becomes ideologically driven; without justice, spirituality risks irrelevance. In my late teens I lived for a year in the Taize Monastery in France and its twin emphases on “struggle” and “contemplation” remain a compelling model for my Christian life. Life choices and commitments, grounded in prayer and worship.

At its heart, the foundation for a Christian life is simple, Jesus himself taught it clearly: love God and love your neighbour as yourself. Justice is the social expression of love. Congregations are called to embody this alternative vision through Beatitudinal living — humility, peace-making, mercy, and truth-telling. Or in Cornel West’s words, “justice is what love looks like in public”.

Embracing weakness and hope

There is grief in the church about declining numbers and influence. Yet perhaps the church is truest to its calling when it shares the weakness of its crucified and risen Lord. Bonhoeffer urged Christians to give offense by siding with the weak rather than the strong, echoing Paul’s insight that God’s power is made perfect in weakness.

The prophetic life must be marked by hope. In the face of so many political and environmental challenges it is hard to believe the oft-quoted dictum: ‘the arc of history bends towards justice’. Maybe the call today is to live ‘as if’ goodness is stronger than evil and life stronger than death.

As a corrective to facile optimism, US theologian Miguel De La Torre warned against an optimism that collapses into despair. His approach is to “embrace hopelessness”, accepting that we cannot save the world; the Christian task is simply to be faithful. Justice is pursued not for reward but because, simply, it is the right way to live and fundamental to Christian identity.

Issues ahead

Among the issues that continue to test the church’s prophetic vocation, three stand out. First is justice for First Peoples — confronting the nation’s original sin of dispossession. Second is the response to climate change, which threatens the poor most severely and challenges us to extend neighbour-love to other creatures and future generations. A third issue is poverty and the extreme and growing gap between rich and poor.

Liberal and liberationist voices

Within the church, two approaches to social engagement can be discerned. The liberal approach seeks to humanise existing systems, working within them for incremental reform. The liberationist approach views the dominant neoliberal order as fundamentally exploitative and calls for resistance at its roots. Both approaches need a place in the church’s ministry, responding to critical immediate needs while witnessing to Gospel values which fundamentally challenge the tenets of neoliberal capitalism. The challenge for those of privilege like me (white, heterosexual, educated, male, financially secure) and for churches like ours, is to acknowledge this honestly, use our privilege for good and work to prioritise voices and perspectives from the social margins.

Conclusion

The prophetic voice of the church will not be measured by numbers or influence but by faithfulness to the God revealed in Christ. The tradition of “radical discipleship” has been formative for me, calling Christians to live in ways that may appear foolish in the world’s eyes but true to the Gospel vision.

To live with confident humility, grounded in truth-telling, prayer, justice, and hope, is to take our place in the company of prophets.

Rev Alistair Macrae is a former Assembly President and Synod Moderator, and current Chair of the Board of Uniting Vic.Tas

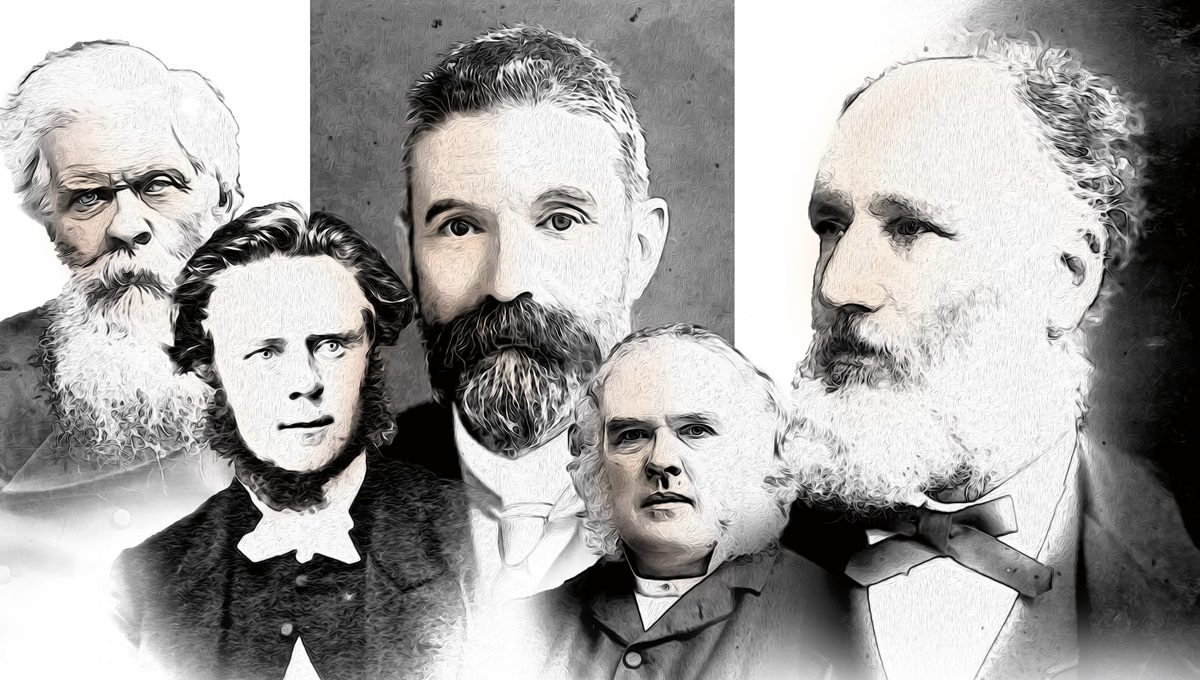

‘Founding fathers of federation’ Sir Henry Parkes, Alfred Deakin, Sir George Dibbs, Rev James Jefferis and Rev Dr Llewelyn Bevan were all strongly committed Christians. Artwork: Carl Rainer

Did the voices of the churches influence the forming of Australia’s 1901 Federation?

By Clive Jackson

The federating of colonies into a Commonwealth of Australia occurred on January 1, 1901. In the two decades before, federation became a political issue that saw public debate, two organised Conventions, a Premiers’ Conference and many local and community meetings.

Most of the literature about federation misses the fact that many of our ‘founding fathers’ were strongly committed Christians who identified with churches. Some leading church people and clergy were involved in the public discussions that took place prior to federation. Some churches covered the topic among Sunday evening meetings that they held in that era, newspaper articles were written, events were attended, and a few church leaders attended the formal conventions.

The man acknowledged as the ‘Father of Federation’, Sir Henry Parkes, was a key parliamentarian from NSW. He was Premier five times between 1880 and 1894. He lobbied and organised to bring about several of the federal conventions and meetings. He died in 1896, never seeing the result. Born in England, in his youth he belonged to the Carrs Street Congregational Church in Birmingham.

Alfred Deakin, Victoria’s most famous campaigner for federation, later became Australia’s second Prime Minister. He was an active member of the Spiritualist movement, and, in his later years, joined the Australian Church, an independent denomination.

Sir George Dibbs NSW Premier (three times between 1885 and 1894) and Anglican Church member attended the 1891 Federation Convention. Both he and NSW MP Albert Piddington, Anglican Archdeacon of Tamworth, continued to promote the federation cause and debated the drafts of the Constitution from a protectionist viewpoint.

Rev James Jefferis, dubbed the ‘prophet of federation’, came to Australia in 1859. He served as minister at North Adelaide from 1859 to 1867 and the senior minister of the Pitt Street Sydney Congregational Church 1877-1889. He was re-appointed as minister to Brougham Place Church, North Adelaide, in 1894. According to writings, he could be regarded more as a strong influencer for the federation cause than a participator in the official conventions. That he had access to political leaders, including Parkes, is without doubt.

Clergy were much more prominent in society in that era, and they could target public opinion. If Jefferis was a leading voice for federation among churches, his advocacy was influential in several ways: he engaged influential friends; he held public lectures; he networked in organisations; and he spoke up at the coincidence of public events very effectively.

As Chair of the Congregational Union of NSW from 1878, in 1880 Jefferis delivered a lecture ‘Australia federated’, opposing abolition of the colony governments. He used the Intercolonial Congregational Conference in 1883 to speak on ‘Australasia federating’. At a meeting in 1889, with Premier Henry Parkes, he spoke on ‘Australia cautiously federating’. Back in Australia in Adelaide in 1895, he delivered ‘The coming Commonwealth’ following a Premiers’ Conference. A Council of Churches, which formed in 1896 in South Australia, added an ecumenical forum on social issues. Jefferis gave another lecture on the Sunday before the Federal Convention in 1897 in Adelaide. That Council recommended a ‘Yes’ vote for the Commonwealth Bill of 1898 and told member churches to ‘pray for guidance’.

On a visit to Sydney, Jefferis used a Pitt Street church anniversary to talk both about federation and about church federation where the Congregational churches were all run semi-independently and the Methodist Church was divided into four similar denominations. Could political unity also serve to bring some denominations together?

“Many of our ‘founding fathers’ were strongly committed Christians,” writes Clive Jackson.

Looking at reasons why clergy and church members were interested in the subject, Jefferis was one who thought of federation as including the South Pacific or a ‘commonwealth’ of British nations. Church mission connections were strong. He and others saw federation as a new Australia taking a place with other nations of the world, providing a guarantee of religious freedom but with an acknowledgement of peoples’ reliance on God.

Another vocal church leader was Rev Dr Llewelyn Bevan. As the Minister at Collins Street Independent (Congregational) Church Melbourne, from 1886-1909, he was a strong advocate for federation within Australia and overseas.

The example of Canada having federated was looked upon as a safe and good model for a stronger nation with a division of powers between federal and province parliaments. The example of the USA was known to be flawed by their own experiences. More local politicians were advocating for home-grown models.

No church came out against federation, however most of the church leaders who spoke in favour were careful to speak only as individuals. Church leaders were interested in federation for the secular issues as well as the religious. When it came to whether there would be a place for God in national life or in the proposed Constitution, the Christian representatives and leaders were speaking up.

In our Australian Constitution today there are two religious mentions, one in the Preamble and the other at Section 116. The Preamble to the Australian Constitution Act 1900 includes words,

“… humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God, have agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth …”.

Section 116 reads: “The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.”

The path to the final wording of both clauses was not a straight line. It began with words by Andrew Clark, (Unitarian) being included in the first draft Constitution in 1891 termed a ‘recognition (of God) clause’. The recognition clause survived the Corowa Conference in 1893 led, in part, by Dr John Quick. Quick, a famous contributor of democratic processes, was also noted as a prominent member of the Bendigo Forest Street Methodist Church. That draft clause was nearly deleted in the Bathurst Peoples’ Convention in 1896, in spite of the cooperation of Rev Gosman (Congregational), Rev Webb (Wesleyan), Bishop Camidge (Anglican) and Cardinal Moran and Rev O’Dowd (Catholic). A summary version was moved by Rev Fielding. The clause was rebuffed at the Adelaide Federal Convention in 1897, being referred back to the colony governments. At this 1897 Adelaide Federal Convention, other ‘recognition’ wording was proposed by Mr Glynn (Catholic). Colonial parliaments supported a recognition clause except Tasmania. The reconvened Convention 1898 in Sydney passed a simplified text re-introduced by Glynn.

The passage of the ‘no power over religion’ clause was bumpy too. Henry Higgins (secularist) with a state-rights viewpoint, opposed mentions of religion and opposed a proposed Federation Bill. From 1897, he negotiated with Barton, Quick, Glynn and others, eventually drafting the s116 wording in 1898.

The important matter here is the thinking behind the wordings. The issues in these years included, whether there be any power to set public holidays of a religious nature; the difference between belief and actions where harmful religious practices could endanger the community; possible grants to schools or hospitals owned by churches; the inviting of which churches’ representatives to government functions or not; the meanings of ‘separation’ of church and state; and the fact that the colonies had some laws of their own about religion.

Two Referenda were conducted. One in 1898 and a second in 1899. The second included Queensland and Western Australia. Both achieved a majority of votes. Church leaders were again active, at least telling their members to vote. The Wesleyan ‘Spectator’ a weekly church newspaper in Victoria published items by editor Rev Lorimer Fison supporting the Commonwealth Bill in the referendum. He quoted the Council of Churches declaring ‘Federation Sunday’ on 22 May, 1898 in advance of the public vote.

A little-known fact is that certificates were issued to those who voted at the 1899 Referendum. One that has survived was issued to a relative of Rev Peter Aumann.

In conclusion, it is clear there was involvement and enthusiasm for federation by many active church leaders including clergy. Bringing this information together shows a public contribution made through churches and the value of being active in the community, as well as being involved in outcomes.

Clive Jackson is a board member of the Uniting Church National History Society and current Membership Officer