In the beginning was the Word … but now there is also art to help explore and expound on the subject of spirituality. Christina Rowntree explains how art and faith are intertwined.

Interview by Stephen Acott

What’s your title?

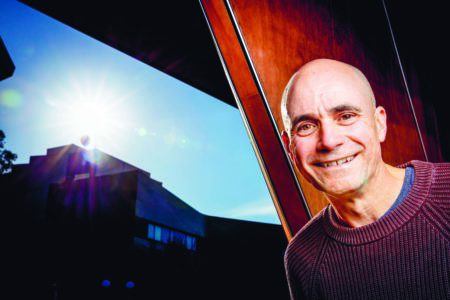

Theology + Arts Ministry, in the Priorities Focus and Advocacy stream of eLM.

When did you begin?

This particular role of developing the arts in the life of our Synod, started in 2005. I’d been working in the Synod before that as an events manager. There was a project looking at where the arts were in the life of the church and out of that came a recommendation that a position be created to continue advocating for the arts, building the networks and promoting the arts in the life of our Synod.

There was already a lot happening, many ministers had an arts practice so, across the forms, whether it be visual arts, iconography, poetry, music, dance, clowning there were people who were expressing their ministry through the arts.

So, what is your background?

I trained in theatre and taught children creative dance for many years. After I’d finished my theatre training I worked as a role player. I had a background in business, so I used my performing arts skills in training and development.

What do you bring to the job?

I bring a facility to work with communities and congregations. I encourage people who have little experience to have a go and get over their reticence. People have really responded so positively, many times surprising themselves and realising how those early experiences of being judged have limited their expression.

A lot of what you do involves visual art.

Ever since I was a child I have loved the visual arts and throughout my schooling, I’ve always followed this passion for the visual arts, learning about the history and theory of art. Now unfortunately I’m a bit of a klutz when it comes to making anything myself, but my studies have given me a good basis from which to engage with visual artists in a range of forms and disciplines. I enjoy curating exhibitions and being a facilitator.

Is what you do unique to this Synod?

It is. There are other people in other Synods who work with the arts and artists, but there’s no other Synod that has been able to fund a position such as mine.

Does every exhibition or event have a religious theme?

There would always be an element of the spiritual, if not the religious. The artists I work with are people who are connected to our work because of their interest in, and passion for, deeper meaning. Most artists have a spiritual element to their work because they have to go to a place where there is emptiness and be comfortable in that place of not knowing. There are very few artists who don’t appreciate the numinous, circling around this sense of the divine.

In the artists’ network I’ve facilitated over a number of years there were people who had no faith, but were still drawn to our network because it was a place where they could connect with others who also valued the spiritual in life.

Have you ever been submitted something and think ‘how is that connected to spirituality?’

That’s where meaning and theological significance come together. And it’s often not just in the visual arts, it could be in the story or the biography of the artist and what they’re trying to express. We had a recent exhibition from Brunswick Uniting Church at the Centre for Theology and Ministry in Parkville where the spiritual significance was the pastoral care of the project itself – the fact that people came after church and engaged in collage art-making.

There were significant relationships developed. People with mental illness or who had other challenges felt included and part of the community. These elements are just as important in that story as the vibrant artwork they produced.

So sometimes the spirituality is in the making, not necessarily the outcome.

This is a really big conversation in the arts, generally. You find a lot of current art practice engages with therapeutic outcomes because people appreciate how transformative the arts are in terms of building community and leading to healing.

Here’s a curly question: what is the purpose of art?

That is a very big question.

It is.

There are many, many answers. If you were to limit the scope of that question to the context of the Uniting Church in Australia – a young church in the Antipodes far removed from the old traditions – we are finding new answers. While we can’t escape our history, with a tumult of antipathy to the arts, we are reclaiming the place of the arts in worship, and our congregational and community life.

If we look to the Indigenous people of Australia, for whom there is no separate word for art – there is no idea that art is separate from life – well how does that blow our ideas of art out of the water? For Indigenous people, art and culture are so infused with life and country and experience that you don’t even have to ask the question ‘what is the purpose of art?’. It’s like saying ‘what is the purpose of life?’.

This is an area I often like to talk to people about. In the Christian gospels there is no place where art is mentioned except when Jesus drew a picture of a fish in the sand. It’s a totally Western concept.

But where Jesus talks about abundant life, my understanding is abundant life is often experienced when the arts are alive in community.

What does art bring to faith?

I’ve thought a lot about this, too. I think the more important question for my work is ‘what is the purpose of art in expressing the faith’ – particularly in our Protestant strand of Christianity. Let’s just think of the past 200 years. The primary forms that were used to express faith were the Word: preaching, writing and, to a degree, poetry and music. They were the acceptable forms with which you could express faith.

In other traditions, the visual arts, design, architecture and different kinds of music and dance were more accepted in expressing faith. So in the young Uniting Church we have the opportunity to question that old suspicion of the arts, which, kind of didn’t want anything to do with the body, didn’t want to see too much colour and movement, didn’t want their music too ornamented. As I’ve worked with people across Australia I can see they are hungry for more ways to express faith through the arts.

When we think of the Catholic Church we think of the Sistine Chapel, when we think of The Uniting Church nothing really springs to mind. Are there any artists you immediately associate with the Church?

It’s a bit unfair to ask for a Michaelangelo, but in Melbourne there’s a marvellous artist called Michael Donnelly. His work is remarkable. There’s a woman called Rachel Peters from Warrnambool Uniting Church who is well known in this Synod, but, really, it’s not about looking for greatness it’s more about recognising that the arts are more and more part of how we do church and how we are church.

Who are some of your favourite spiritual artists?

I really don’t like saying one over another. That said I must mention Kirk Robson, who died way too young in 2005 in a car accident. Kirk started the Torch Project, a community arts organisation. He was recognised by the Australia Council as a leader in Community Arts and Cultural Development practice.

You’re getting visibly emotional speaking about him.

Yes, sorry. He was a remarkable performer and his legacy continues through the Kirk Robson Theology and the Arts Memorial fund. I get emotional because he could still be contributing. He was such a trailblazer in that he managed to build relationships with Indigenous people to drive a project not just alongside their community, but bring them right into the heart of it.

How do artists go about being exhibited?

Contact me on (03) 9340 8813 or email [email protected].