By Andrew Humphries

Every five years, Australians everywhere wade through a mountain of paperwork as the Federal Government’s Census takes a snapshot of the economic, social and cultural make-up of the country.

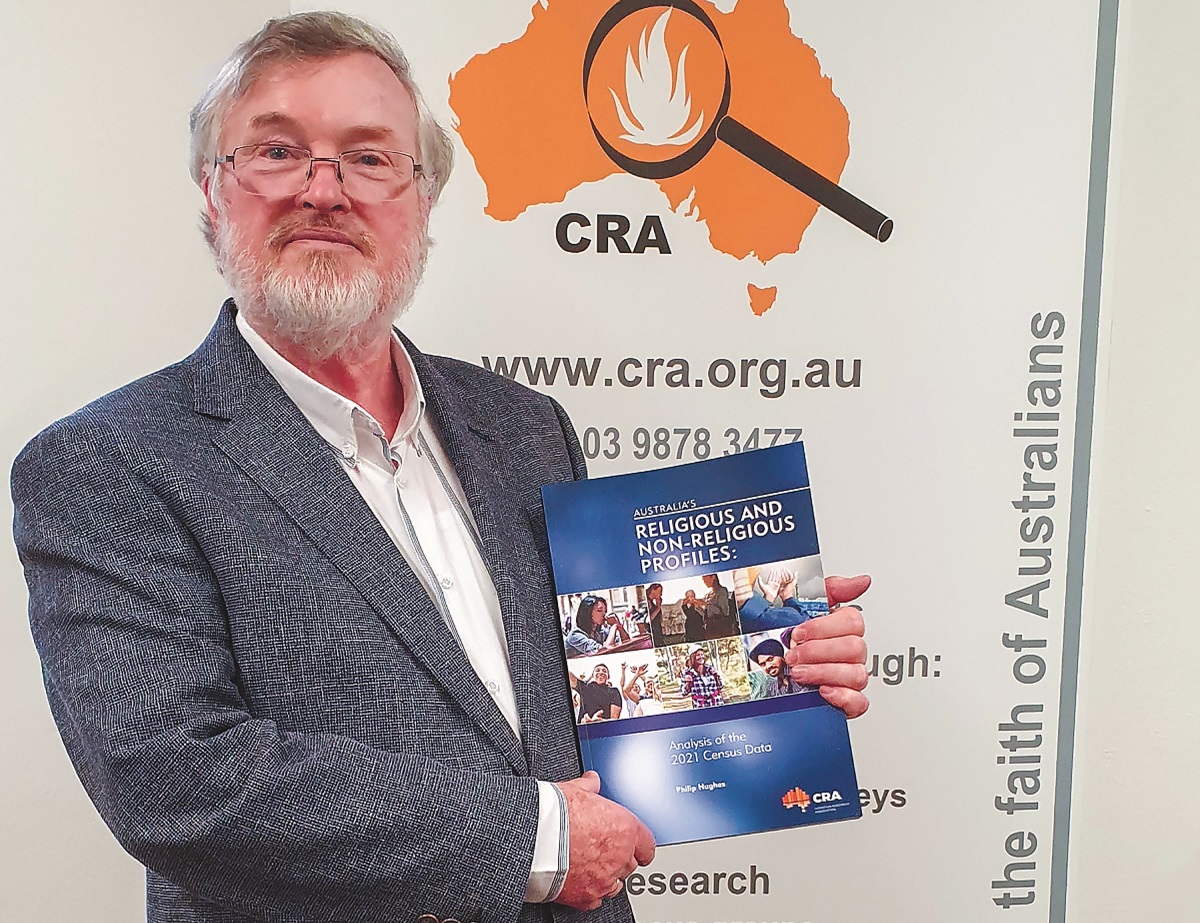

And on each occasion since 1991, former Uniting Church Minister Rev Philip Hughes has become the “Census Detective”, as he takes a deep dive into what the data tells us about religion and its place in Australia.

After every Census, except for 2016, Philip has put his thoughts together in a book which analyses where religion sits in the lives of more than 25 million Australians.

His latest publication, ‘Australia’s Religious and Non-Religious Profiles: An Analysis of the 2021 Census Data’, was launched at the end of March and provides a timely insight into the changing face of faith in modern Australia.

While his latest analysis is a useful tool for all denominations, Philip hopes it will be particularly helpful to the Uniting Church in guiding future planning.

“There is definitely useful material in it because of how broad it is, and therefore how accurate it is in terms of determining the identification of trends that are occurring in society,” Philip says.

“Clearly it’s something all denominations find of great use as they try to get a snapshot of what’s happening today.”

So what do the Census figures tell us and what can we glean from them to help guide planning for the future?

They tell us, firstly, says Philip, that there has been a dramatic drop in the number of Australians who willingly identify as Christian.

“What’s happening across the board is that the percentage of people identifying as Christian has declined significantly,” he says.

“It was 61 per cent of the population in 2011, and it had dropped to 44 per cent by 2021.

“There is only one denomination that has actually grown in terms of the percentage of people in the population who identify with being Christian, and that is what we would describe as the Oriental Christian group.

“That is due largely to immigration by people from the Middle East, and that Christian group has been growing quite rapidly, while all others have declined.”

“It is accepted that everyone can have a faith or no faith, and there is nothing inherently wrong with any way of living,” says Rev Mat Harry.

Rev Mat Harry is the Synod’s New and Renewing Communities Catalyst and points to the experience of his daughter Shalisa as an example of that changing face of faith in Australia.

“With brown hair, my youngest daughter Shalisa really stands out as the sole Anglo girl in her high school class,” Mat says.

“All of Shalisa’s classmates were either born overseas, or their parents were.

“Many are of different faiths, Islamic, Christian, and a variety of other faiths, or no faith at all.

“Within class Shalisa speaks freely and openly of her faith and involvement in church life, just as openly as her Islamic friends talk of Ramadan and their faith practices.

“It is accepted that everyone can have a faith or no faith, and there is nothing inherently wrong with any way of living, it is just a part of life and an expression of all of us “doing, or being, ourselves”.

If, as Philip points out, the Census tells us that there has been a significant drop in those who identify as Christian, the next question, then, is how concerned by this should we be?

Philip is in no doubt about the answer, even if it’s one we might not want to necessarily hear.

“Yes, I think alarm bells should be ringing for all denominations because it’s a larger decline than we were anticipating,” he says.

“We’ve seen the drop occurring over the years and it has been occurring mostly with people in the 25 to 35 age group.

“What happens is that young people grow up and the person who’s filling in the Census about them in the household describes them as sort of Anglican or Uniting Church or whatever, and then when they are old enough to fill in the Census themselves, they put down ‘no religion’.

“So that’s been happening for the last 40 years or so and has been a general trend, but what this Census shows is two patterns that we haven’t seen before.

“One is that it’s not been just the 25 to 35 age group that’s been dropping out, it’s been people of all age groups, and there are equivalent numbers dropping out in the 35 to 45 and 45 to 55 age groups, and even a lot of older people who are dropping out.

“That’s indicative, I believe, of a wider cultural change throughout our society that it’s not just this creeping change from the boomers on, there are more significant changes.

“The other pattern that is also interesting is that it’s happening in rural areas just as much as it is in urban areas.”

Philip says the influx of migrants who bring their faith to Australia with them has benefited a denomination like the Catholic Church, rather than the Uniting Church.

“Their faith tends to become stronger once they leave their former country and arrive in Australia and that’s because they will obviously look to connect with people of similar language and values to their own, and those people are often found in religious organisations here,” he says.

“The Census tells us that 280,000 immigrants have arrived in the past five years who identify as Christian and a lot of them are Catholic and have had a huge impact on that Church, much more so than on the Uniting Church.

“So the Uniting Church hasn’t benefited as much from immigration as the Catholics, or the Anglicans or Baptists have done so.”

The Uniting Church is one of a number of mainstream churches that have seen a drop in numbers.

For the Uniting Church, then, the Census statistics paint a sobering picture.

In 1961, 20 per cent of Australians were either Methodist, Congregational or Presbyterian, yet by 2021, just 4 per cent were Uniting, Congregational or Presbyterian.

The decline in the Uniting Church is one of the fastest among the denominations, and between 2011 and 2021 across Australia, there was a fall from just over 1 million members to less than 700,000, a drop of 37 per cent.

So, where have these people gone?

“Well, a few have moved to other denominations, but the majority have gone into the ‘no religion’ category or simply written ‘Christian’ without going into further detail,” Philip says.

It leads him to ponder the deeper issue of the place of religion in Australia in 2023, particularly for those churches we might consider as being more mainstream.

“A number of denominations, such as the evangelical and charismatic churches, have not declined so rapidly, whereas the more mainstream churches have tended to decline much more rapidly,” Philip says.

“I think the best explanation for that decline actually lies in values, and there’s been a major shift in people from traditional pro-family values to values of personal fulfilment, and within that sense of personal fulfilment the church doesn’t necessarily have a place.

“It’s not seen by the majority of people in the population as actually supporting that personal fulfilment in a significant way, whereas what’s happening with the evangelical and charismatic churches is that they are still supporting the traditional family values and people are still attending those churches because they find support for those traditional values.

“These people become even more enthusiastic about their churches as the place where they feel safe and where their values are maintained.

“However, these churches have never engaged more than a tiny part of the Australian population, and there is growing distance between them and the population as a whole.”

This trend towards personal fulfilment is one Mat also says needs to be considered when considering the role of religion in contemporary Australian society.

“’You do you’ is almost the expression of our time,” he says.

“Society at large is person-affirming, meaning that no one understands the individual better than oneself, so do not judge, categorise or label an individual in any way.

“It is up to the individual to decide for themselves how they seek to be understood, and this then extends to religious faith and expression.

“We live in a context of a ‘multifaith and no faith’ milieu.”

Faith-based organisations like the Uniting Church need to work out what they can offer Australians in the future, says Rev Philip Hughes.

For a progressive Church like the Uniting Church, all of this presents an issue which needs to be addressed, says Philip.

“What it raises for the more open and liberal progressive churches, like the Uniting Church, is a question of what is it that we offer society which they don’t necessarily find elsewhere?” he says.

“By any measure the Uniting Church would be considered a progressive church and therefore it doesn’t attract people so much who feel that they’re in a minority in society and want to sort of maintain a difference from the values that most people in society hold.

“On the other hand the question then becomes, what is the attraction, and I think it’s not that people sort of reject the Uniting Church, it’s more that they don’t find sufficient reason to actually go to it.”

Mat says a move away from Christian observance has also had a part to play in many people turning away from faith-based entities like the Uniting Church.

“Whereas previously the Christian Church was afforded privilege, with public holidays given for Christian observance and seen as sacred, and the Christian story reinforced within cultural practice, this is no longer the case,” he says.

“Football is played on Good Friday and Christian religious education is seldom a feature of public school life.

“Christian movies are very rarely shown on television at Christmas and Easter.

“We can no longer assume that people understand the story of Christ.”

Christian author and communicator Melanie J Saward says a recent study shows the extent of the problem facing many churches.

“Many statistics have emerged over the last few years that have painted a jarring picture of the state of faith for Millennials and Gen Z,” she says.

“But none quite so shocking as a study completed by the Barna Group recently, finding that 75 per cent of young Christians will leave church.

“What can’t be denied is that there is something missing in the Millennials’ and Gen Zs’ experience of faith, that is often observed through their relationship with the Church.”

While those figures paint a disturbing picture, Melanie says there was a consistent thread running through the reasons given by those people who remained committed to their relationship with faith.

“Unlike other studies, the Barna Group study listed common factors present in the 25 per cent of people who stayed,” Melanie says.

“These included: eating dinner together five of seven nights a week as a family; serving with their families in a ministry; having one spiritual experience in the home during the week; being entrusted with responsibility in ministry at an early age; and having at least one faith-focused adult in their lives, other than their parents.”

The nurturing of a deep faith is crucial, says author Melanie J Saward.

It is this depth of faith, says Melanie, that must be nurtured if future generations are going to continue the practice of worship.

“In my latest book, ‘Deep Faith Resilient Faith’, I examine what I believe to be the cause of this phenomena, and the missing piece is depth,” she says.

“It has always been a temptation in our Christian culture to become preoccupied with external matters and not those of the heart.

“From the day the church began, there were smaller sections that concerned themselves with rituals, and in the generations just prior to Millennials, church attendance has been the universal sign of commitment to Christ.

“The five factors involved in keeping people committed to Church are all signs of a whole community discipling a child, that is parents, church leaders, and the larger church community.

“Truly, they are signs of depth and the priority to instil a deep faith in the next generation.

“Depth of faith is critical, as scripture proposes many times: it was the depth of the soil that determined the response to the seed (Mark 4:5), and it was deep digging that stabilised the house built on the rock (Luke 6:48).

“And so we must explore for ourselves what a deep faith looks like, so that we can exemplify it for the next generation.”

Like Melanie, Mat says it’s the church as a community that can best represent the depth of faith that is available for people to tap into.

“Research suggests about 25 per cent of the population claims to be lonely at any time, and it’s often described as a loneliness epidemic,” he says.

“Congregations are well equipped to help address this epidemic.

“When a congregation acts as a community of grace and care, accepts people for who they are, is fully inclusive in practice as well as theology, and gathers in ways that make sense and are inspiring for the people they are alongside in mission, such congregations are well positioned to bear witness to the glory of the story of Christ and respond to this multifaith and no faith milieu.

“It is well-positioned for those open to exploring spirituality to do so with us.”

As the Uniting Church ponders the drop in its membership, Philip says it must be prepared to tackle some hard truths if ground is to be regained.

“It’s a matter of looking at ways we can best offer people a sense of meaning,” he says.

“Can we support people through issues of mental health and can we really build a strong sense of supportive community among people?

“So it’s really a matter of reflecting now on what is the place of our churches in society as a whole.

“One of the things that I’m very keen to look at much more closely, and which I would suggest to the Uniting Church that it considers, is how do people gain their sense of meaning today, and my suspicion is that a lot of it happens in small groups and close relationships.

Small groups and relationships may be emerging as a preferred form of worship, says Rev Philip Hughes.

“My sense is that what’s declining most rapidly are those churches which are sort of just local neighbourhood churches which may be too big to be just small groups but, on the other hand, aren’t the big megachurches that can offer large numbers of small groups.

“I think the whole concept of bringing people into smaller communities where they find people who are supportive or with who they can relate, and with whom they can take action together in relation to social justice issues and that sort of thing, is really important.

“The patterns of Sunday morning services with preaching and so on is, I think, a declining pattern that’s not working so well for many people.”

The question, then, is where does Philip see the Uniting Church placed in 25 years?

Will there, in fact, still be a Uniting Church?

“I think a lot depends on what directions we take now,” Philip says.

“Certainly one of the struggles is that a lot of Churches decline to a tipping point where they just can’t continue financially their models of being church, which are dependent on having a building and a Minister.

“And so that just becomes unrealistic and therefore they merge, and often in merging they lose their sense of identity and so decline further.

“And it’s likely that in another 25 years there’ll only be a few of the larger Churches left.

“Certainly the immigrant churches will be maintained over the next generation, so the Samoan and Tongan churches, the Korean churches, Chinese churches and so on, but even they may decline after the first generation.

“Whether they can transition to being multicultural churches is certainly an issue.

“I think the Uniting Church will survive and if it continues to sponsor new expressions and small group activities which are less dependent on the traditional structures and forms there is hope for it to continue to play a significant role.

“It means that leadership will have to be different into the future and that the patterns of the past aren’t necessarily going to work.

“We need to look for less institutionalised ways of being a Church and look for those smaller groups who will be supportive of each other but also find a sense of meaning through values and social action.

“It needs to be a case of promoting churches to try new things out, which becomes even more important into the future.”

As the Uniting Church stands at a crossroads, Mat says it needs to take comfort in and build on the fact that for many young people it represents a faith-based organisation most in touch with their own values and view of the world.

The younger generation is being urged to fly the flag of faith.

“The Uniting Church finds itself in a very interesting position,” he says.

“Yes, more people are not identifying as Christian in Australian society and less people are identifying with a Christian denomination.

“However, there is much evidence to suggest that more of the younger generations are open to spirituality in all of the forms that spirituality takes.

“Yet, due to the Uniting Churches broadly inclusive theology we may suggest that our denomination is the most person-affirming.

“The UCA’s understanding of the message of Jesus is one which is more closely aligned with how the broader society understands the individual.”

While it might sometimes be facts and figures that drive the debate on religion’s place in modern Australia, strip it all back and you get to the very essence of what matters.

For Melanie, it’s about the current generation carrying the flag of faith for those to come.

“The fact is the next generations need us,” she says.

“They need those of us who have come before them to demonstrate through the life we live, the kind of depth and meaning that a faith in Jesus can bring.

“They don’t need us to nag them, to judge them, to be frustrated by them.

“They need us to be willing to take up our cross, forego our comforts and go deeper than we have ever gone before, because the gospel has always been enough to satisfy all of us, from generation to generation.”