By Stephen Acott

In 1999, as Mary Neale was kayaking down a river in North America, she came upon a waterfall. She knew it wasn’t too steep so she went down without a second thought.

And then something tragic happened.

Or so it seemed.

When the nose on Mary’s kayak hit the rocks at the bottom, it became wedged, pinning Mary about 3m underwater. Worse, the force knocked her unconscious.

Fortunately, the group she was kayaking with saw what happened and immediately rushed to retrieve her. But it took them about 15 minutes to get her out of the kayak and on to land. All that time, Mary remained underwater. Dead.

Or so it seemed.

Mary’s body was purple and bloated, confirming her lack of oxygen. Needless to say, she wasn’t breathing. All seemed lost, but her friends went straight to CPR.

Ten minutes later they were still at it. Eleven minutes … 12 minutes … at what point do they acknowledge the inevitable and stop?

Thirteen minutes … 14 minutes … 15 minutes …

And then something miraculous happened.

Or so it seemed.

Mary gasped back to life. She had been brought back from the dead.

Or had she?

That is, at what point are you “dead”? Is it when you stop breathing? Well, science says no. Science says it is when you reach a loss of cellular life – in other words, when your brain stops functioning. But we’ll be going into more detail on that in a minute.

First we should acknowledge the miracle of Mary’s life-after-death episode. How do you explain that?

“I had been without oxygen for 30 minutes,” Mary says. “The statistical likelihood of my survival should have been zero. It took a number of hours, but my friends got me to the hospital. My husband was told I probably wouldn’t survive the night, but I did.

“Statistically, I had zero chance of surviving with zero brain damage, but I never had any brain damage. I made a complete recovery.”

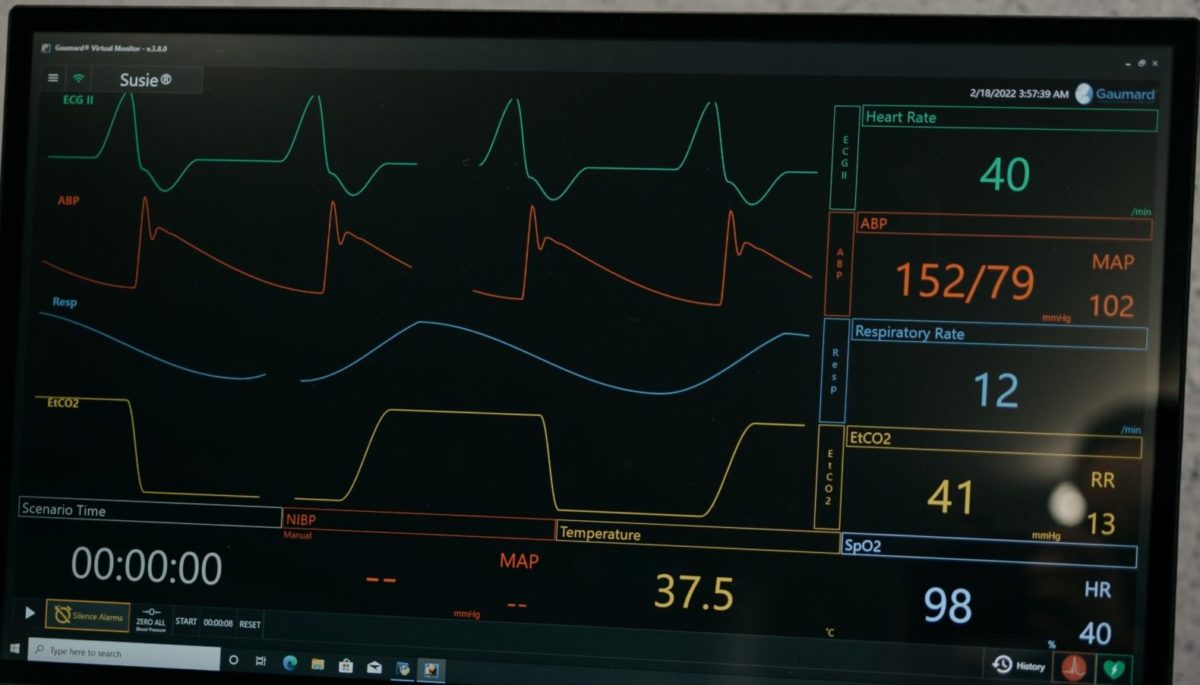

Lines on a heart rate monitor show a person is alive, but what happens when they “die”?

Mary’s experience is the centrepiece of the first episode of Surviving Death, a six-part series available on Netflix that has divided audiences – religious and secular.

And one of the reasons there are dissenters is for what the program doesn’t do and doesn’t say. Mary’s tale isn’t a miracle. It’s unusual, yes, she’s luck to be alive, but there isn’t a doctor well versed in underwater medicine who would raise an eyebrow.

Dr Chris Vernon is a former president of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society and one of those doctors with eyebrows unraised.

“If the water is cold enough, people can survive for 40 minutes completely submerged,” he says.

“In fact, when I started practicing medicine in the 1970s, when we were performing heart surgery we would put people in ice-cold baths to lower their temperature – this reduces the heart rate and amount of oxygen required by the brain.

“Mary would have received a sudden rush of cold water through her nose and mouth which would have instantly cooled her brain. That’s what saved her. I’m not surprised to learn she survived and that should not have been portrayed in the show as some sort of miracle. It wasn’t.”

OK, but that’s only half of Mary’s testimony – and the other half is impossible to debunk. It’s impossible to prove, but equally impossible to disprove.

So let’s go back to the moment Mary became stuck at the bottom of that waterfall. What did she experience once her heart stopped beating?

“My torso was plastered to the front of the kayak,” she says. “I could feel my bones breaking. I thought, ‘I should be screaming’, but I wasn’t.

“I felt no pain, no fear, no panic. I felt more alive than I’ve ever felt. I could feel my spirit peeling away from my body and my spirit was then released up into the heavens.

“I was immediately greeted by a group of ‘somethings’ – I don’t know what to call them. They were spirits. I didn’t recognise any of them, but they had been important in my life story, like a grandparent who had died before I was born. They were so overjoyed to welcome me in love. These beings take me down this pathway, which was covered with hundreds of thousands of flowers. It was exploding with every colour of the universe.

“There was an absolute shift in time and dimension. Every second expanded into all of eternity. The pathway went to this great dome structure. I believe I was in heaven, or whatever you call it. I had an overwhelming sense of being home.

“At the same time, I could look back at the river, where my body was still submerged underwater.

“I did not want to go back down to my body. I had a very physical sensation of being held and comforted and everything was fine, but the beings told me it wasn’t my time, that I had more work to do on earth and I had to go back to my body.”

Mary Neale recalls being welcomed to another place when she “died” while kayaking in North America.

There is a lot to unpack there. Mary talks about a spirit being released, being greeted by ‘somethings’, being welcomed in love, a shift in time, a dome structure and looking down on her body.

And all of this in just half an hour.

“People in science think you can’t possibly believe in anything supernatural,” Mary says. “When I went to medical school I would have defined death as ‘death’ – meaning physical death – but what happened to me changed my definition of death significantly. I don’t believe we know everything.”

Death gets a bad rap in western culture. It’s inevitable, we know it’s coming, we just hope it’s not coming tomorrow – unless you are in horrific pain, physical or mental. But, by and large, death is not something we tend to dwell on.

A Jewish proverb cautions us: “If you start thinking of death, you are no longer sure of life.”

Even the Bible tends to quickly switch the narrative from death to life or, rather, encourages us not to see death as an end, but rather the beginning of life eternal.

“For God so loved the world that he gave his only son, that whoever believes in him should not perish, but have eternal life.”

That of course is John 3:16. But then there is Ezekiel 18:32 – “For I have no pleasure in the death of anyone, declares the Lord God, so turn and live.”

Turn and live. That is a strong, empowering, uplifting command.

John Flett is co-ordinator of studies – Missiology and Intercultural Theology – at Pilgrim Theological College. He has studied religion formally for 17 years and been a visiting professor in India, Romania and the DRC and also taught in Germany, South Korea and the US. That background has gifted John a perspective on life, death and everything in between that isn’t confined to standard western teaching and thinking. But it doesn’t mean John has all the answers. In fact, straight answers aren’t his schtick. Ask him a question and he’ll answer it eventually, but not before several tangents are thrown in and negotiated.

John has a lot of theories – all of them well considered and many of them thought-provoking – but even some topics leave him stumped. Well, one at least: death.

When asked what happens when someone dies, John, who has conducted countless funerals, replies simply: “I have no idea.”

But he does have some thoughts. Interestingly, he points out there are multiple Christian views on the subject.

“For example, one of the key tenets of the Christian faith is resurrection,” he begins. “So what is resurrection? A number of people will say that’s just a metaphor, so it’s a way of speaking about how you live your life now, rather than what happens in some sort of afterlife.”

John Flett from Pilgrim Theological College.

This seems to marry with Ezekiel 18:32.

“In Christian theology, death is related to this notion of sin and sin has something to do with the breaking of a relationship with God and the breaking of that relationship means the loss of life. So, what is life? Therefore, one of the questions that death promotes is ‘what is life?’. What does it mean to be alive? To be living?”

There’s one of those thought-provoking questions.

“But what happens if sin never happened and, therefore, death never happened?,” John continues. “How many people would be alive and walking around now? So one of the parts of that is death is an essential part of life.”

OK, but what about Mary’s testimony. Let’s go back to the unpacking. First question is obvious: Does John believe Mary?

“I believe she believes it,” he says. “I don’t think she’s making it up.”

Yes, but do you believe what she is saying is what happens?

“I don’t know.”

OK, what about some of the other things, such as the dome structure and being taken down a pathway covered with flowers. Is that heaven? If so, do you believe in heaven?

“Another way of thinking about death is each person has a notion of a soul, something that’s eternal,” John begins.

“In my opinion, that’s just paganism, it’s not related to Christianity. You don’t find any discussion of a soul within the biblical text. It’s a legacy of Greek ways of thinking about ‘what is eternity?’. But some people believe you have a soul and that soul is eternal and when you die that soul goes somewhere. Either to heaven, where you run amongst the flowers, or hell, where you get burnt alive.

“Believing in such a thing as a hell, where a God who is supposed to be loving now subjects you to eternal torment, is not a position I would hold.”

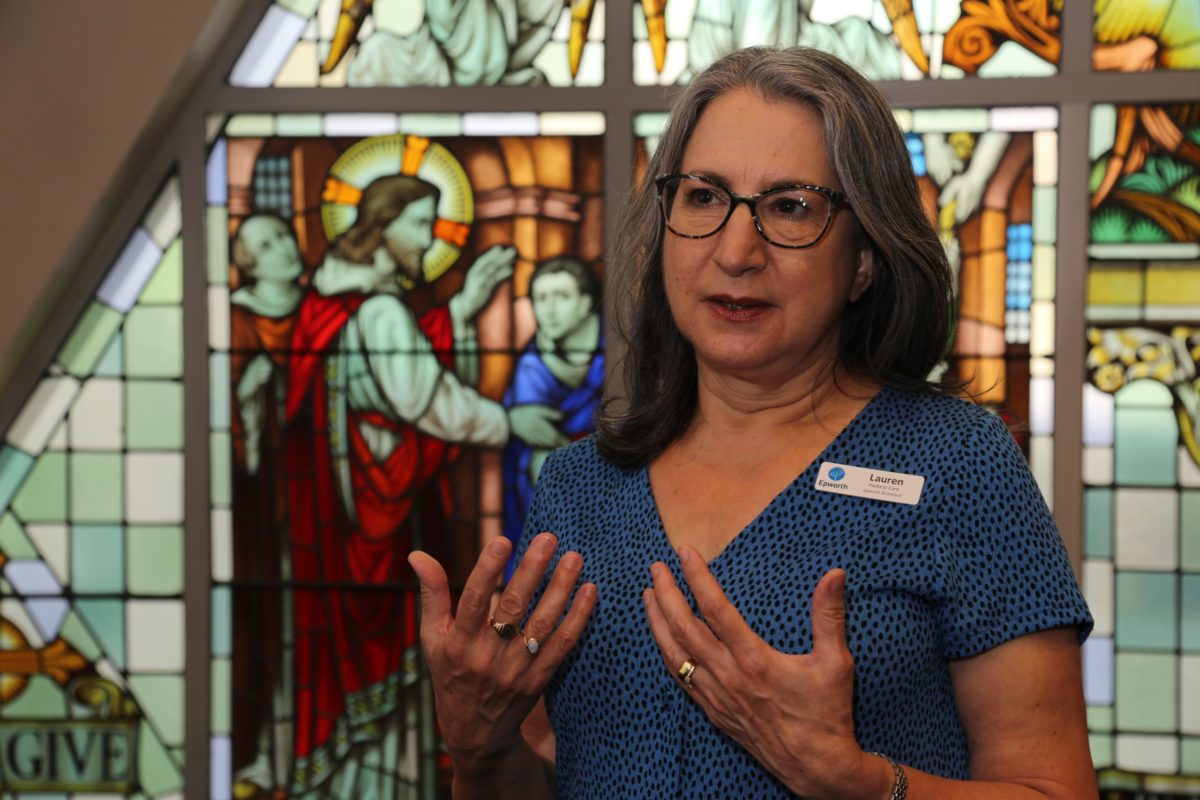

Lauren Mosso is the senior chaplain/pastoral care coordinator at Richmond’s Epworth Hospital. Lauren has been in the job for six years, a job which means she deals with death daily.

Lauren says Surviving Death reiterated her belief that death is not something to fear. When asked what happens when we die, Lauren has an answer: “We return to the source of love that we came from.”

Is that what some people call heaven?

“Heaven has been set up as the opposite of hell, and I don’t believe in hell,” Lauren says.

“Heaven has almost become a prize or a reward for good people rather than everybody. I have a very generous understanding of God’s love, that it encompasses everyone. I believe we all end up there regardless of what we’ve done, because God’s love is bigger than ours.

“Some Christians believe you need to accept Christ into your life to get to heaven, but the Uniting Church is a broad church. So we will have some on that end of the spectrum and I’m probably sitting on the other end of the spectrum with a more open view about that. I believe there are many paths to the one God. That’s what grace means to me.”

Epworth Hospital senior chaplain Lauren Mosso deals with death on a daily basis.

Lauren says she has never seen someone die and be brought back to life, but has had an “after death” experience.

“One of my friends from high school – I went to high school in New Jersey – died at age 40 and it was really tragic circumstances,” she says. “And I was here in Australia looking in the mirror and I had this feeling that she was with me, letting me know she was OK. She was at peace. It was unexpected and totally out of the blue. I couldn’t see her, it was just a feeling.

“I’ve heard more than one person talk about experiencing loved ones present in the room. It might be that they’re now unconscious, but their family members say ‘this is what he’s been talking about’.

“I believe you can feel the presence of someone in the room.”

Near-death experiences are not new and have long been documented. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, author of the groundbreaking book On Death and Dying, which was first published in 1969, said she had interviewed thousands of patients who had near-death experiences after she had a similar experience.

“Death is just a different form of living,” she said. “It’s a new birth, a new beginning.”

And these experiences are more common than you might think. One study found about 10-20 per cent of people whose hearts stopped would report a near-death experience.

In order to discuss near-death experiences, it is important to define death. When is someone unequivocally dead as a Dodo?

Chris echoes the “cellular death” definition. He says when the heart stops, the brain remains active for a short period. Interestingly, the opposite is also true. These seconds – and they are only seconds – are crucial when discussing near-death occurrences. It is in this moment that people seem to have these paranormal experiences. And this is where time – or our perception of time – is vital.

This is something John is keen to explore.

“Time is not this lineal concept,” he says. “You are always interpreting time. For example, if you’re sitting in a meeting and it’s dead boring and you keep looking at your watch, time seems to move very slowly. It’s just dragging on.

“I like rugby and I hate the last two minutes in a close game if you’re in the lead because that two minutes seems to never end. So time is a thing that you experience and think about.

“I also remember falling out of bed as a child. I had a dream and I dreamt that I was falling, eternally falling – hours and hours of falling – and then I hit the ground and woke up. So the dream was me telling myself I’m falling out of bed. Now to fall out of bed takes a quarter of a second, but in that quarter of a second my brain was able to hyper process that I’m falling and puts it in the form of a dream and that quarter of a second is hours in my dream. But that wasn’t a near-death experience – it was a kid falling out of bed experience.

“Another example is driving on black ice and sometimes when you hit the brakes you start gliding and you know you’re going to hit something but the adrenaline kicks in and everything slows down. These are mundane experiences that happen to people every day.”

We are told that just before you die, your life flashes before your eyes. If true, it is another example of time bending to our unconscious will. That is, what seems like a personal movie reel lasting minutes is in fact something that lasts only seconds, milli-seconds even. It would appear the brain is radiantly alive in this moment. It is certainly not dead. In fact, it would seem it was never more active.

Many people talk of having an out-of-body experience after coming back to life.

Mary spoke of this “shift in time and dimension” as she journeyed to that dome accompanied by loving spirits and looked down upon her mortal body.

“Time is a fascinating concept,” John says. “Brain science says when you get older you experience time more slowly than when you were younger. One of the theories is that as you get older and you learn more your brain ends up creating more pathways.

“Think of a baby. It has not had any experiences so the distance between two points is a straight line, but as your experiences occur your brain starts to navigate them so the electrical currents through your brain take longer. It might be one billionth of a millisecond longer but that causes you to experience time slower.”

Many people who have “died” and come back to life speak of having an out-of-body experience.

In 2005, a woman called Pam Reynolds was undergoing major surgery and “flatlined”, which her neurosurgeon, Dr Robert Spetzler, explained to her meant her heart and brain had stopped functioning. But Pam “came back” and the flat line on the hospital monitor suddenly burst back into action.

Pam made a full recovery and, upon regaining consciousness, started talking about what she had experienced when the monitor flatlined. This caught Robert’s attention. How could Pam have “experienced” anything other than a deep, anaesthetic-induced sleep?

But Pam was able to detail extensively what happened during her surgery; who was in the room, what instruments they used, etc, etc. Robert was astonished.

“Pam’s eyes were taped shut and she was wearing moulded ear pieces, yet when she was revived she could recount in great detail what happened to her during surgery – things only someone in the room could have seen,” Robert says.

“Her ability to describe what went on during surgery is inconceivable, considering the state she was in. Pam was clinically dead.”

Dr Peter Fenwick, Neuropsychiatrist at the University of Cambridge, has been studying near-death experience for about 40 years. He says Pam’s experience is supported by thousands of similar testimonies and challenges science’s fixed position that when the brain stops functioning consciousness also shuts down.

“Materialistic science says (life is) all brain,” he says. “So when the brain stops functioning you can’t be conscious, but during these near-death experiences you get these very wide expansions of consciousness, even when the brain has ceased to function. So it can’t be all brain.”

Chris, whose day job for the past 40 years was an anaesthetist, says he never witnessed anyone speaking of a near-death experience when resuscitated after “flatlining”. However, one of his close friends and colleagues told him he had such an experience.

Dr Peter Fenwick challenges science’s fixed position that when the brain stops functioning consciousness also shuts down.

Chris, who is a staunch pragmatist, particularly when it comes to medicine and scientific “fact”, says his friend’s story gave him cause to reconsider his definition of death.

“We are both Port Adelaide supporters, so when he was telling me this, I asked him if he now supported the Crows. He looked at me strangely and said ‘no, why do you ask?’ And I told him if he now supported the Crows I knew he had become delusional.”

John does not place any significance on the out-of-body experiences highlighted in Surviving Death. He says it certainly gives no credence to any suggestion of people floating heavenwards only to be turned around.

John, who experienced significant trauma as a child, says he has had several PTSD-induced out-of-body experiences during his younger years.

“They are saying this person was brain dead and they had this near-death experience but, as a kid who experienced trauma, I distinctly remember leaving my body and looking down upon myself,” he says.

“PTSD means you get locked into a prematurely limited time, you never get away from the events you experienced. You are always looping them over it and over again, re-experiencing them, and they change your perception of where you stand and how you are to be and act.

“In my experience, you know why it’s occurring because you are trying to escape from something you can’t and your body does a whole range of clever things to try and escape from it. I don’t believe in any of this paranormal experience, but I believe very strongly in the power of trauma and the mind to create a whole range of different experiences.”

Death is often regarded as the Last Word. The Last Stop. Once you go through that door, your life and everything associated with it, ceases to be. That is not the Christian position, however. In fact no religion holds that position to be true. Religion is at pains to proclaim death is the end of chapter one, not the end of the book.

Again, go back to John 3:16. Eternal life.

In 1910, Henry Scott-Holland, a London priest, gave a sermon titled Death The King Of Terrors and part of it has been turned into a poem and recited at funerals ever since.

“Death is nothing at all, it does not count,” Scott-Holland said. “All is well, nothing is hurt, nothing is lost. One brief moment and all will be as it was before. How we shall laugh at the trouble of parting when we meet again.”

As John says: “The most important thing is life, not death. We are all going to die. Death is not something we need to worry about.”

As foolhardy as it is to distill religious philosophy into a sentence or two, it is pertinent to consider non-Christian perspectives when it comes to death.

Sogyal Rinpoche, author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, says “perhaps the deepest reason why we are afraid of death is because we do not know who we are”.

“When a person does not know what they stand for and their purpose, they may be afraid to die because it means the end of their time to figure out these states of being,” he says. “If you have a deeper understanding of yourself and your purpose in this world, you can greet death as the path to something more.”

Elsewhere, Sogyal writes that “death is a mirror in which the entire meaning of life is reflected”.

“Because of this sentiment, Buddhists spend their lives working to understand who they are and what is important about life and death personally and in general,” he says.

Sogyal Rinpoche writes that “death is a mirror in which the entire meaning of life is reflected”.

John says there are parallels in Christian theology and also uses the mirror analogy. Life informs death, and vice versa.

“We are taught that death is a mirror upon your life,” he says. “You don’t know what your life is until it’s complete and you look back. When we are talking about death we are talking about the orientation of life.

“This notion of a soul is that it’s eternal – it was there before you existed and it will be there afterwards. But how is it impacted by life events? Life is this rich, complex thing and we’re always trying to grapple with what it is. The discussion of death helps us do that.

“Look at grief – it’s a mind-bogglingly difficult thing for people to deal with. Some people can’t process it and it never disappears. When we get to death, we are trying to order life. I have done many funerals where the father has died and it is obvious he has not been a nice person and his family are there just to see him off to hell. That he will now pay for the sins that went unpunished in his life.

“At Sunday School, we are taught hope. That when we die we hope something good is going to happen. But what are we hoping for? Where do you see value lie? And it is precisely these questions that are orientating you now.”

Islamic faith closely mirrors Christianity’s position on death and the existence of an after-life. In a nutshell, when someone of Islamic faith dies they will eventually be raised from their graves and brought before Allah. If they have been good they go to Jannah (Paradise), the rest got to Jahannam (Hell).

Hindus, of course, share with Buddhists a staunch conviction in reincarnation. Not so much an afterlife, as another life. Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda says “man will find that he never really dies”. “His soul persists beyond death; he will have no more fear of death,” he says.

“Man must conquer this illusion and know that the dead are here beside us and with us, as much as ever. It is their absence and separation that are a myth.”

Swami raises two topics worth exploring in more detail: the concept of soul and the concept of spirits. Are they one and the same?

Surviving Death devotes two episodes to Mediums, one to “seeing dead people (ghosts) and one to reincarnation.

Lauren says she has never visited a medium, but might be open to it. She says her views on the subject “expanded” as she watched the program.

Lauren Mosso with fellow pastoral carer Claire Davies.

“What I was mainly thinking about is ‘are the mediums picking up something from the other world?,” she says. “Or are they picking up the deep consciousness of the people who are present, who hold these memories of cherished ones in their hearts?’ Either way, it’s a mystery.

“I guess the skeptic in me wonders if they picking up information through pastoral care-type conversations they’ve had with people before they came. We glean all kinds of information when we’re listening deeply to another person.

“I work in this area of spirituality and listening to people’s spirit and what gives them hope and what animates them and so the program perhaps has broadened my understanding of spirituality.

“Certainly with the mediums, that was fascinating. It’s not my thing, but it’s a thing. It’s helpful to our sense of respect for others to broaden our experience and understanding by exposure.

“As for reincarnation, before that show, I would’ve thought ‘no, we only get one chance’, but the show was very persuasive. As a Christian, I believe we’re each unique and precious, so how could somebody else reappear in this way? Their life is supposed to be finished and they’ve sort of taken over this person. It doesn’t make sense.

“Also, it’s possible that it was contrived. It’s possible they picked up all this information on the internet. It was very interesting – persuasive, but not decisive.”

John says soul and spirit are two separate entities. Well, actually, that’s not true. He says there is only one entity: spirit. There is no such thing as a soul.

He acknowledges that certain translations of the Bible use the word “soul” a lot, but, as stated earlier, puts this down to other ideas being projected on to the text. In fact, he says everything in the Bible speaks against soul.

“The whole of the biblical text is about embodiment, not disembodiment,” he says. “And it’s about incarnation, taking on flesh. What happens with this philosophical way of framing ‘soul’ is that you have this God who is external, silent, doesn’t move – is a massive monad and doesn’t care about our ‘little ant lives’.

“So when you talk about soul you are buying into this thinking that one day I’m going to die and my soul is going to disappear. So your history has no meaning and your body has no meaning and you destroy your own life.

“Nothing about you is important, except this funny little kernel that belongs to something that doesn’t move. And that’s the thing that’s going to get extracted and go wherever. I just don’t believe in that. And part of the reason is, central to the biblical narrative is the fact that God became a human being and had a history and part of that history was this horrific death. And another is that this is the truth about humanity.

“Think about Ukraine and the bombing of these child cancer hospitals – if I believe in soul, none of that matters because those children are just little monads that are going to float up into wherever. And that means we allow pain and injustice and suffering and simply move on, unless it affects us personally and then it suddenly becomes important.

“But that’s not the biblical message. The biblical message is somehow God became human and died horrifically and the power of God lies there, in that weakness, in that history.”

The Bible tells us that “God became human and died horrifically and the power of God lies there, in that weakness, in that history”, says John Flett.

Spirit, John says, is something altogether different. And it’s something we share with other cultures – First Peoples, for example, although First Peoples take the concept of spirit to another level.

“Western Christianity is very good at creating a major division between Creation and God,” he says. “So you have earth, which is material matter, and this spiritual being, which is God. To Indigenous peoples there is this middle range of spirits that includes ancestors and the ancestors have died, but they stay there in the spirit realm and continue to direct the community.

“So, if you asked them ‘is there life after death?’ they would look at you and say ‘are you an idiot? Of course there is. Look, here’s my ancestor walking right beside me’. They are dumbfounded that the West is so materialistic and flat that they say what you can see and touch is the only reality. So they look at us and think we’ve impoverished ourselves because we think we have nothing except when we die.”

John acknowledges there is a “force” that can’t be seen, but can be keenly felt. He’s felt it himself and, once he felt it and listened to it, his life was never the same. The force he speaks of is what we label a “Calling”.

“I am an ordained minister and I have a Calling,” he says. “To use some of this horrible abstract language, there is some ‘force’ that has said to you ‘this is the direction your life should go and for that you will be paid less than a plumber, you will do 40 years of theological education for people not to believe a word you are saying’.

“The only reason I would take up this occupation is if I believe there was a Call.”

When it’s suggested that differentiating between soul and spirit could simply be splitting hairs, John leans forward, pauses, and says very quietly, but firmly: “No, they are two very different things.

He then leans back and explains. The passion in his, er, soul?, causes the volume in his voice to return to normal.

“The Bible talks about the livingness of God, of God’s glory. God is a living God. The Easter resurrection is all about the livingness of God. So the livingness of God is about spirit, about breath. About history. About relationships.

“Soul says I can have a relationship with God without anyone around me. But that’s not theologically accurate. What I’m talking about is spirit and spirit is contingent upon my relationship with you.

“Galatians 3:28 says there is no more Jew or Gentile, neither slave nor free, there’s no more male and female and what it is saying is the community is made up of your enemy and your enemy is the one that’s going to bring you God. Now that’s a hard ask and it’s very different from a soul. That is saying I have no spirit, no spiritual life and no access to God without my enemy.

“Western materialist society loves the essence thing, it loves the idea that we can boil something down into its essence and once we have its essence it’s captured. We know exactly what it is. But what happens if we can’t capture it? The Bible talks about the spirit of God and that’s not something you can capture.”

When considering history, John Flett asks: is God in charge of time?

John says spirit is something unseen but alive. It’s within you right now as you are reading this. And, where the concept of soul says that entity remains within you, your spirit is within and without you. It is something you pass on to everyone you meet – whether you and they like it or not. That’s what keeps it alive – and that’s what keeps us “alive” after we have “died”.

“I have children, I have a wife, I have relationships,” John says. “Those relationships means my spirit is within them, and theirs within me. This conversation means I’m part of you, whether you like it or not. Putin’s part of me because I have been reading up on what’s happening in Ukraine. We have these massive, inter-connected relationships and some of them remain after we die.”

History is important to John. Ask him a question and he will invariably tangent into history and sometimes won’t realign himself with the question. He’ll even do it if he asks himself a question. For example, he asks, unprompted: Is God in charge of time?

“Well, if the answer is no, what’s the point of history?”, he answers himself.

“Where does the meaning of all these lives come to? Your life too has no meaning. So why is Hitler worse than me? What’s our basis of judgment? Sin is a category that applies to us all and it gets magnified the more bad we are or more good we are.

“We can go through history. Look at Donald Trump. I think the guy is pure evil, but is he worse than me? Is Captain Cook good or evil? You’ll get a ton of people saying he’s evil and you’ll get just as many people saying he should be celebrated.

“I think life counts. History counts. It has meaning and it changes people. But what happens after our life is over? I just don’t care. The tenet of justice relies on the notion that God is just, that God is love. So a loving and just God will make judgments according to the criteria of love.”

Lauren says her job has taught her several things about death and our relationship with it – a relationship we mostly don’t acknowledge until death is staring us in the face. But once we do acknowledge our mortality, indeed once we accept and make peace with it, our life is enriched. And that also can be true for those who are with us when we die.

Equally, death sometimes ends any hope of reconciliation, leaving those left behind with a hole in their life.

“We are told hearing is the last sense to go, so we encourage family and friends to touch the dying person and talk to them as if they were listening,” Lauren says. “It’s having that sense that they’re still able to experience life right up until the last breath.

“One thing we’ve found is ruptured relationships are still troubling at the time of death and it seems like there’s a message in that for us about how we live. The living still have this unresolved conflict after the person dies and no one to resolve it with. It’s quite sad.

“What we find with pastoral care is if people can come to accept death is happening, it’s much easier for them. Even if a whole lot of stuff is unfinished, if they come to that place of acceptance that they are dying, then they can just stop worrying about it and enter into the experience with their family and the loved ones, whoever is able to be with them.

“They’ll be wrapped up in love and focus on the presence of love with them right now and let that love carry them. They have the privilege of doing that, but we also see traumatic sudden deaths where people don’t have any time to do any of that. I’m often meeting the family when the person has already died and I haven’t met that person. Meeting loved ones after sudden, traumatic deaths or drawn out traumatic deaths are difficult. Those are ones that stay with me and I need a lot more debriefing.”

“God is a God of love, not a God who causes things to happen to people,” says Lauren Mosso.

Lauren says her faith helps her to carry on. She has had people tell her ‘how can you believe in a God that would do that to someone?’ And in those moments she reminds herself that “God is a God of love, not a God who causes things to happen to people”.

“I believe what happens to people is random, it’s not a test,” she says.

“I believe illness happens for all kinds of random reasons, it’s not visited upon people for any kind of awful reason. That doesn’t mean someone who’s in this experience is going to share that belief.

“Just because God doesn’t micromanage, doesn’t mean God doesn’t love us. And it’s awful, there’s nothing that makes this any better. The idea of you’ll go to heaven when you die doesn’t make it any better in the moment when you’re going through the suffering.”

Lauren says if witnessing so much death has taught her anything, it is to embrace life. Not with a “you’re only here once” mentality, but to look within you for what gives your life meaning and follow that lead.

“Death does not have the last word,” she says. “We proclaim that at a Christian funeral and even in leading a secular funeral, there’s something about being part of the continuum of human existence.

“The people on Surviving Death who had died and come back to life death seemed to have a real spiritual conversion of some kind,” she says.

“Something seems to have kicked in about the purpose of being here. They started to live differently and started not sweating the small stuff and were more present to what was happening in the here and now.

“My experience is, when people are dying, they don’t say ‘I’m so grateful I achieved this and this and this. And I worked so hard.’ They don’t say that. What they say is, ‘I’m so grateful for my family. I’m so grateful I had these people in my life and the love we have.’ That’s what’s important to them as they’re preparing to die.

“When I visit somebody at random, you don’t know what they’re going to talk about, but they often tell you about their life and the high points and the low points and what they’ve experienced and, for them, it’s to make meaning of their life. What’s it been about? We call this a ‘life review’.”

Indeed. And each of us will answer that in our own way. There are no right or wrong answers. But maybe, just maybe, there is a right and wrong road. Most of us won’t be afforded a near-death experience to act as a rehearsal. We won’t be taken take down a pathway covered with flowers exploding with every colour of the universe. We’re going to have to wing it.

So what should we do? Maybe we should listen to Ezekiel. Maybe we should turn away from death and head toward life. Turn and live.

The last word on death surely should be “live”.