By Andrew Humphries

Mardie Townsend often talks to her son Paul.

And that’s when the tears come.

After all, a parent should never have to bury their child.

“When we are at Bonnie Doon, I often go for a walk and when I walk past Paul’s cairn I say (in my head), ‘hi Paul’, and he replies (in my head) ‘hi Mum’, his voice, his inflection and intonation all as clear as a bell,” Mardie says.

“That’s when my eyes fill with tears.”

Paul died on July 1, 2016, his death from a drug overdose ending a life of rich potential blighted by the shadow of schizophrenia.

When Ormond Uniting Church congregation members Mardie and her husband Ron talk about Paul, they tell a story of love and hope, of sadness and despair, and a level of anger that, right at the end, Paul was let down in his hour of need.

With brutal honesty they also talk of a sense of relief when Paul died, bringing to an end nearly 20 years of unimaginable stress dealing with an adult whose actions, at times, pushed them to the absolute limit.

“We always imagine our children will carry on after us, and to have to bury your child is so confronting,” Mardie says.

“Paul’s death was a shock and we feel terribly sad about it on an ongoing basis but, yes, there was a sense of relief because it was a traumatic 19 years as his schizophrenia took hold, and we were constantly on edge trying to find a way through it all, for him and for us.”

Their love for Paul, though, was unconditional and his story is one they want to share, not to seek pity, but because on the streets of every town and city there are a thousand Pauls, each one fighting to hold their place in the world while gripped by mental illness.

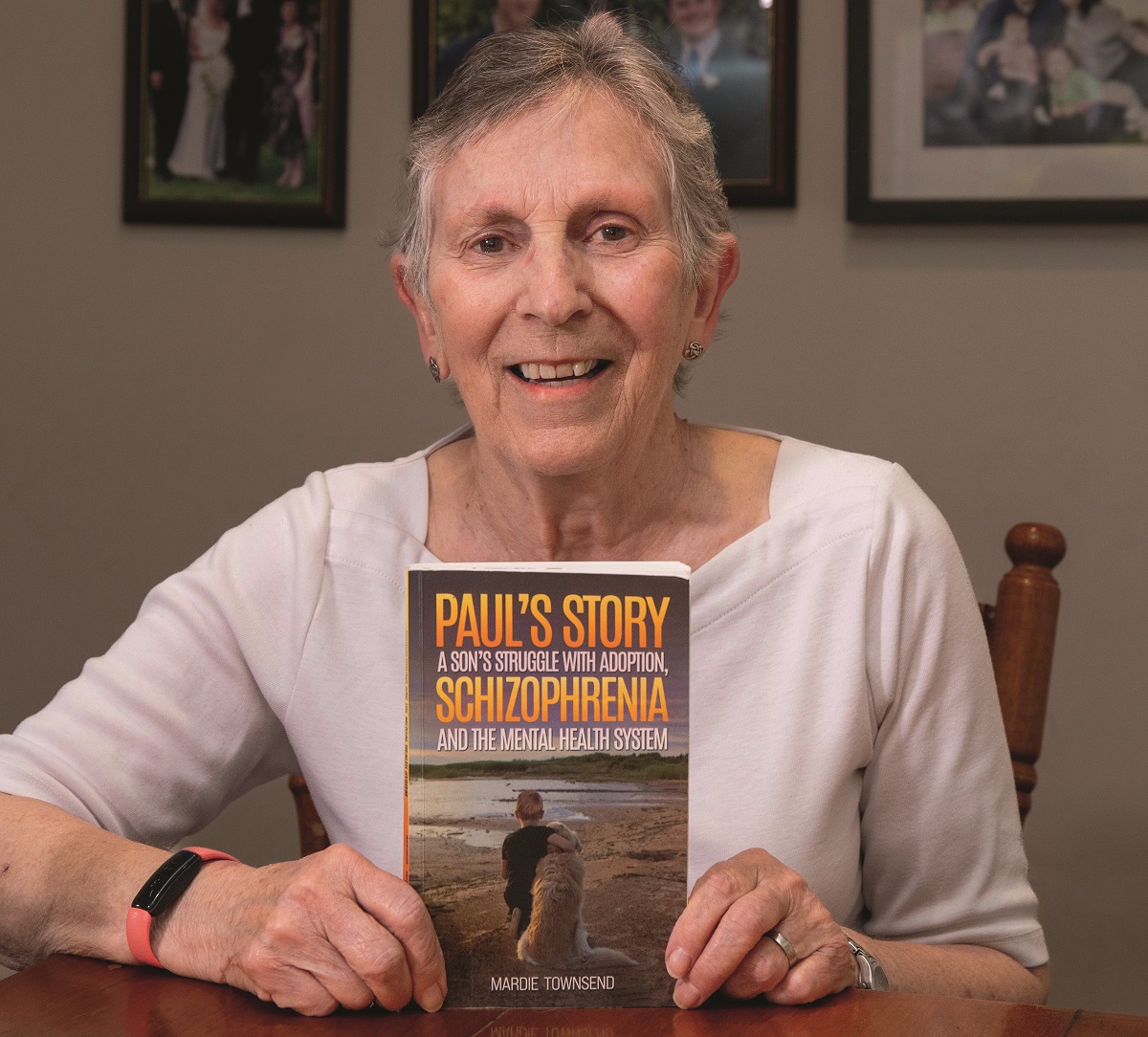

Last year Mardie published a tribute to Paul, ‘Paul’s Story: A son’s struggle with adoption, schizophrenia and the mental health system’, hoping for a sense of closure but also wanting his story to be a catalyst for change around how we deal with those with a mental illness.

If every story must have a beginning, Paul’s begins in 1979 when he was adopted at six months of age by Ron, a regional youth worker with the Uniting Church in Gippsland at the time, and Mardie.

Paul joined a loving family, which also included Ron and Mardie’s two children, Ruth and Joel, who embraced their new sibling wholeheartedly.

Paul’s early months after his birth, though, had been traumatic.

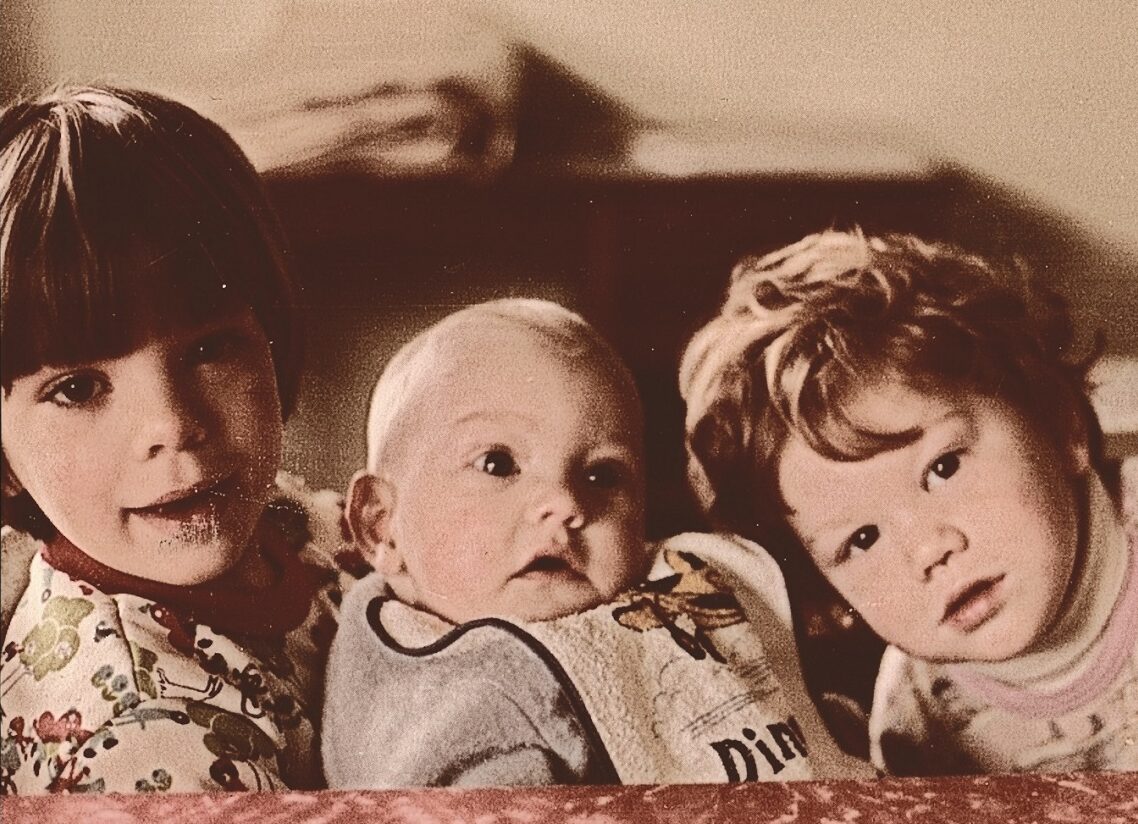

Mardie and Ron Townsend with a photo of their son Paul (middle), and his brother Joel and sister Ruth.

His mother had fought her own battle with schizophrenia, resulting in treatment involving electro-convulsive therapy and medication while pregnant with Paul, which undoubtedly had an impact on her unborn child.

Unaware she was pregnant, Paul’s mother had been prescribed modecate, a drug used to treat schizophrenia.

Mardie believes feeding problems and agitated behaviour in Paul’s first few weeks were a result of his mother’s use of modecate.

Paul enjoyed a happy and largely uneventful childhood, beginning with a family move at the end of 1979 to Mansfield, where Ron took up the position of Uniting Church Minister.

It was near Mansfield that Ron and Mardie designed and built a house at Bonnie Doon, based on the concept of environmental self-sufficiency.

They still own the property today and, for Paul, it was often a haven in his adult years as he sought escape from his mental illness.

While some of Paul’s behaviour during childhood had been concerning, it was in 1997 that the first obvious signs of mental deterioration appeared, a year in which he had his first contact with his birth mother, a permanent resident in a Sydney mental institution.

Mardie suspects Paul’s distress at the situation involving his birth mother, and his use of marijuana to deal with that, was the catalyst for what were to become serious mental health issues for the rest of his life.

She recalls an incident around this time in which Paul was taken by ambulance to hospital after a psychotic episode in his bedroom.

“Despite his stereo being turned up to almost full volume, when I opened the door to tell Paul his dinner was ready, I could hear him wailing and keening above the music,” Mardie recalls.

“I still have a clear vision of him, wild-eyed and rocking backwards and forwards, seemingly unable to move from his couch, and reacting as though he was being attacked.”

For the next 19 years, schizophrenia was Paul’s constant and unwelcome companion, preventing him from reaching his full potential and achieving what he wanted in life.

This is what fills Ron and Mardie with the greatest sadness when they consider what might have been.

Paul’s life, they say, was one filled with sunshine and shadows.

Shadows were cast by his abandonment as a child, his birth mother’s mental illness, and his own schizophrenia, but there was sunshine at times around achievement and enjoyment, friends who stuck by him, and parents and siblings who loved him deeply.

Mardie admits, though, that life with Paul was lived on a knife’s edge as his schizophrenia worsened, never sure when and why he would lash out.

“Much of the time you never knew what was coming with him,” Mardie says.

“I recall one time we had visitors from England around for dinner and we invited Paul over because he knew the daughter of this couple.

“So he came along and, at one point, somebody said something completely benign, which he misinterpreted and went completely off the handle about, and it became quite a stressful event.”

Paul as a baby with Joel and Ruth.

The uncomfortable truth, they say, was that Paul could also be violent, on one occasion punching Mardie as she drove him home from a meeting.

“I would say that Paul wasn’t by nature a violent person, but the voices and demons in his head sometimes became too much for him,” Mardie says.

It was during the most difficult times that their faith, and the support of their Church, carried Ron and Mardie through.

“I’m sure our faith was tested at times but it didn’t disappear,” Mardie says.

And for that she offers heartfelt thanks to the Ormond congregation, their Uniting Church home for many years.

“In a sense, our faith and our church community became absolutely pivotal in sustaining us,” Mardie says.

“We’re very active within the local church and that Ormond community is absolutely essential to us.”

That support, and the support of the wider community, helped them deal with their grief when they said farewell to Paul at his funeral in 2016.

“Church Council secretary Heather Baxter read the parable of the prodigal son and I just sat there sobbing because it was such a remarkable elucidation of Paul and of how God is so loving,” Ron says.

“That love of God was there even more, despite this terrible tragedy of Paul’s death.

“Our Minister Andrew Boyle then spoke and he absolutely nailed this message around how our gracious God takes on board our suffering and enables us to rise through that suffering.

“I’m convinced that God will love my son Paul until the end of time.”

If one positive thing emerges from Paul’s death, Ron and Mardie hope it will be the opportunity to start a conversation around how we view people with mental illness and what better processes can be put in place to ensure they receive the best treatment possible.

Mardie’s book has thrust her into an advocacy role, and the story it tells has been taken on board by a number of universities, keen to incorporate it into their social work courses.

The book, she hopes, can be a small piece in a larger jigsaw puzzle representing change.

“I wanted to highlight the issues facing people in Paul’s situation, and their families, and to make readers aware that people with mental illness are real people, instead of just statistics and cases,” she says.

“I also wanted to draw attention to the state of the mental health system so that people might feel better prepared to deal with everything around it and press for improvement within it.”

A school photo of Paul.

As they reflect on Paul’s life, and death at the age of 37, Ron and Mardie take comfort in the fact that their love for him, though tested deeply at times, never wavered.

It is this that gives them solace when they consider what they might have done to provide a different outcome.

“I think every parent looks back on their role and says, ‘well, could I have done that differently?’ and there are certainly instances with Paul where we could have acted in a different way,” Mardie says.

“But if we look at an overall picture, Paul had a loving family who did its best to support him and cope with the challenges his mental health issues posed.

“We’re not perfect, but we did our best and it was pretty good.

“When Paul was not psychotic I’m sure he knew that he was loved deeply by us, but in the midst of psychosis who knows what demons were in his head, and I think that’s the challenge with a disease like schizophrenia.

“In his own journal Paul writes that the words ‘I love you’ from his parents fell on (his) deaf ears, but I think he knew, when he was well, that he was loved by us.

“We loved him unconditionally and endlessly and, at times, that love was tested, through Paul’s abuse, derision, violence and disengagement, but it remained strong to the end of his days and still lives on.

“There was much to love about Paul and he had such potential, but we never got to see the best of him because mental illness dominated him.”

Ron and Mardie want people to know what Paul meant to them and how mental illness robbed him of the opportunity to lead a full, and fulfilling, life.

“We only discovered relatively late in his life that Paul was incredibly artistic and some of his paintings were astonishing,” Mardie says.

“Paul was a talented, loving and caring young man who had abilities which were never able to be displayed to their full potential because of his mental illness,” Mardie says.

“That is true of so many people, and if we supported people with mental health issues better we would be unlocking enormous talent.

“The message is that with people like Paul we see their mental illness, but what we don’t see is the person, their talents and their strengths, and it’s time we opened our eyes.”

‘Paul’s Story: A son’s struggle with adoption, schizophrenia and the mental health system’ is available through Amazon, Booktopia and Benn’s Books in Bentleigh.

Mardie hopes Paul’s story will further the conversation around mental illness.

Paul fell through the cracks

On the day that Crosslight spoke to Ron and Mardie Townsend, they were digesting the news of the death in New South Wales the previous day of a 34-year-old man with mental health issues.

The man, who had a long history of schizophrenia, was shot dead by police at a medical centre at Nowra after he approached them armed with a weapon.

For Ron and Mardie, such incidents immediately bring to mind thoughts of their son Paul, and what might have been if he had received adequate care and support during the final stages of his battle with schizophrenia.

When Paul was released from high-level hospital mental health care and returned to his unit on June 14, 2016, they knew with almost complete certainty that it would not end well.

In fact, his discharge that day started a clock ticking towards his death, less than three weeks later.

On July 1, Paul was dead, found by police and his sister Ruth on a couch in the unit after a drug overdose.

Ron and Mardie acknowledge that hindsight is, as the saying goes, a wonderful thing, but firmly believe it was the lack of a carefully organised plan for Paul’s ongoing support and care upon his release that consigned him to his fate.

While Ron and Mardie have no issues with Paul’s treatment in hospital, it was that lack of a suitable plan upon his release that leaves them angry.

“On the whole the in-hospital care was done reasonably well and was as good at it could have been,” Mardie says.

“The issue is with the discharge process and post-hospital and community-based care.

“It’s a patchwork approach, and very inconsistent.”

The truth is, they say, that Paul was is no position to look after himself after seven months in a psychiatric facility and it was vital that he had proper support in those crucial first weeks after his release.

That support should have begun with a period of time in transitional care, before any thoughts of a return to his unit, they say.

Yet, to their astonishment, Ron and Mardie were told that not only would Paul be returning immediately to his unit, his only support would be two brief meetings each week at the regional authority’s mental health support service, meetings which Paul would be required to make his own way to.

Paul didn’t just fall between the cracks because of that lack of support, he fell down a deep chasm which ultimately led to his death.

“Paul was discharged after seven months in hospital, much of that time in a locked ward,” Mardie says.

“We were assured there would be support for him when he was released but, in fact, there was nobody there for him, no crisis assessment team or any other team following him up every day.

“All of a sudden, he is out in the community and he has to walk to their facility twice a week to see someone.

“If they thought he needed to be in transitional care but couldn’t provide it elsewhere, then they needed to provide it in his unit.

“It seems that there’s a big gap between people coming out of hospital and living in their own home, and it’s an inconsistent approach, where some people get the care they need and other people fall through the cracks.”

Ron and Mardie say only a drastic overhaul of the mental health support system will mean there are less stories like Paul’s, and more about those with mental illness who are able to thrive once released from care into the community.

It also requires a fundamental shift in the mindset of the many people who already have a pre-determined view of those struggling with mental illness.

“I think so many problems arise because people look at those with mental health issues and say ‘oh, they’re nutcases or fruitcakes, it’s best just to ignore them and have nothing to do with them’,” Mardie says.

“But the reality is that mental health issues of one sort or another affect one in four people in their lifetime and that’s a huge statistic.

“Just about every family at some point in their life will have to deal with mental health issues.

“The difficulty with mental illness is that we don’t understand it and we judge people because of that lack of understanding.”

“As Christians we need to ensure that we do not add to the burden and stigma of mental illness with bad theology,” says Rev Andy Calder.

Statistics represent real people

By Rev Andy Calder

Mardie Townsend’s book, ‘Paul’s story: a son’s struggle with adoption, schizophrenia and the mental health system’, is an honest and moving saga of a family’s love and support for their son, and his struggle with identity and meaning.

It is also a saga of their struggle with the Victorian mental health system.

Mention in the book is made of Paul’s connections with various community groups, including the Uniting Church, and activities including Sunday School and the National Christian Youth Convention.

Statistics tell us that 1 in 4 Australians will suffer from a mental illness at some point in their lifetime.

For some people this is a one-off occurrence, for some their illness is episodic, and for others their mental illness is life-long.

These statistics are not just numbers, they are real people, people who are members of a congregation, be it UCAF, youth group, men’s group, church council, or pastoral care group.

Some of these people are Sunday School teachers, ministers, committee members, and worship leaders.

They are also partners, friends, parents and children, and, like all illnesses, mental illness impacts on those who care and support, many who also look to the community of the church for support, care and compassion.

There will be people in our communities of faith who never reveal to the community they have a mental illness and others for whom their mental illness is all too obvious because of the way their symptoms are manifest.

One of the burdens of mental illness is the stigma and fear. It is why some people fear telling others about their illness and it often affects the care we offer.

As Christians we need to ensure that we do not add to the burden and stigma of mental illness with bad theology.

Mental illness does not result from lack of faith, or a weak faith.

It is not caused by turning away from belief or a lack of trust in God and it does not continue because the person has not prayed enough.

The Uniting Church Synod of Victoria and Tasmania, through its congregations, agencies, various missional outreaches and advocacy to government, has historically sought to support and welcome people labelled with mental health issues: people who so often have experienced exclusion and alienation in a range of settings.

This is inspired by the gospel imperative: ‘Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it’ (Hebrews 13.2).

Supplementing the Church’s responses above, Synod submissions in 2019 to the Victorian Mental Health Royal Commission advocated for many of the changes called for in Mardie’s book, as well as greater recognition of spirituality’s importance in the lives of people within the mental health system.

The Synod has also produced a ‘mental health kit’ resource, designed to support congregations in their response to people with mental health issues.

Its aim is to enhance welcome and support, as well as acknowledging the gifts, insights and contributions people labelled with mental illness can offer.

Mardie concludes: “Paul’s life, perhaps more than most people’s, was lived through a mixture of sunshine and shadows”.

This painful story of lived experience is an honouring of Paul’s life and a poignant reminder that much more change is needed.

Rev Andy Calder is Disability Inclusion Advocate within the Synod of Victoria and Tasmania