By John Bottomley

Many people are puzzling over the underlying reasons behind Scott Morrison’s so-called ‘grab for power’.

I suggest these reasons are based in his formation in Pentecostalism and patriarchy. Both were hidden in plain sight when the former Prime Minister sought to justify his decision to appoint himself minister of five separate ministries in his government. Speaking at a press conference, Morrison described himself ‘steering the ship in the middle of the tempest’.

Secular commentators have made fun of Morrison’s use of the word ‘tempest’ in a now familiar response that may reveal their lack of biblical knowledge, and their ignorance of Morrison’s brand of Christian faith. For the image the former PM used to justify his actions aligns his intervention amid the pandemic chaos with the story of Jesus saving his followers from a life-threatening storm.

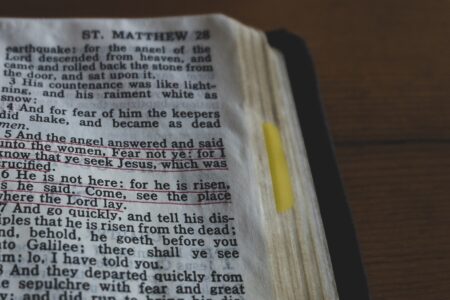

The word ‘tempest’ is viscerally planted in my memory from my childhood Sunday school story of Matthew 8:24-27, where the King James Bible version of my youth reads, ‘And, behold, there arose a great tempest in the sea, insomuch that the ship was covered with the waves: but he was asleep.’

Thus the word ‘tempest’ reveals how Morrison came to see himself when facing a crisis. Perhaps this image also comes from Morrison’s youth, because this word has disappeared from most modern Bible translations of the story of Jesus calming the storm. The Matthean text is about Jesus’ power, but Morrison’s belief allows him to assign that power to himself – with self-righteous conviction.

In a February 2019 article in ‘The Monthly’, Tasmanian historian James Boyce offers an instructive insight into Morrison’s Pentecostalism. Boyce describes how Pentecostalism rests on an intimate personal experience of God that confers on a believer such as the former PM, the power of the Holy Spirit to lead Australia, and save the nation from the power of evil.

Further, Boyce argues it is intrinsic to Pentecostal strategy to maintain secrecy about a believer’s use of the power of the Holy Spirit in the cosmic war against the Devil. In the tempest brought by the pandemic, it would appear Morrison’s strategy is based on his belief that Jesus is in charge of the ship with Morrison commissioned to steer the country to safety, guided by the power of the Holy Spirit.

When trying to respond to this insight, the social policy problem we have is the widespread fear of criticising the ‘private’ beliefs of Morrison’s religion. In a recent 774-radio conversation between the ABC’s Virginia Trioli and David Speers, Trioli suggested to Speers that several confidants of Morrison had suggested to her Morrison’s actions could be better understood through an analysis of his religious beliefs.

She cautioned that this was a ‘sensitive’ space to enter, but Speers shut it down immediately, saying no-one had raised this with him. The possibility that a person’s religious beliefs could form their political practice appears to be “off-limits”: a proposition mainstream Christianity has mostly championed in its failed attempt to maintain its power in the private sphere of people’s lives.

This taboo-like reticence to investigate politicians’ religious beliefs perpetuates what Boyce called ‘a dangerous delusion’. Boyce had pointed to the problem of not investigating Morrison’s beliefs a full year before the pandemic hit Australia, especially Pentecostalism’s belief in satanic evil, but Boyce’s analysis was not taken up to any extent in either secular or religious media.

There is no shame in feeling powerless during a global pandemic. But sadly, that is too often how men formed in the beliefs and practices of patriarchy feel in times of powerlessness: shame. Pentecostalism’s belief in its followers’ access to the power of the Holy Spirit is a great fit with patriarchy, justifying every exercise of male power with a divine mandate.

However, this is an ideological ‘fix’ that does not address patriarchy’s solutions to the reality of powerlessness, so men like Morrison bounce between behaving like a hurt little boy as victim – blaming ‘everyone’ for expecting too much of him – or playing the all-powerful bully – expanding his power by stealth and using it to create a narrative for his selected journalists that place him as the hero at the centre of the tempest. Perhaps it is no wonder that Morrison’s public justifications for his actions appear confused and contradictory.

The public anger and disgust at Morrison’s actions in this episode are palpable, but I am not persuaded that commentators, critics or politicians have taken us much closer to understanding the ‘why’ behind his actions. There is every possibility that Morrison believes the pandemic is the work of the devil, and his actions in taking the helm of the ship of state in the tempest represent a totally misguided attempt to save Australia from satanic forces.

The implication of this possibility speaks into Morrison’s rush to confront China on the pandemic’s origins, and may speak to his need to the secret deal to ditch the French submarine contract in favour of British and US nuclear submarines. There may be more at stake here in understanding Morrison’s ‘grab for power’ than his undermining of vital conventions in our democracy.

John Bottomley is a Uniting Church in Australia minister and Chairperson of the Religion and Social Policy Network of the University of Divinity.