By Andrew Humphries

On May 21 last year, Anthony Albanese began his speech as newly elected Prime Minister of Australia by making a heartfelt promise to our First Nations people.

“I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet,” he told the nation.

“I pay my respects to their elders, past, present and emerging.

“And on behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.

“We can answer its patient, gracious call for a voice enshrined in our Constitution.

“Because all of us ought to be proud that amongst our great multicultural society, we count the oldest living continuous culture in the world.”

Fast forward nearly 12 months and that “patient, gracious call for a voice” continues to dominate discussion around the country.

In February, Albanese said he expected the country to go to a referendum before the year is out on whether that indigenous voice to parliament should be included in our Constitution.

The Uniting Church wholeheartedly supports a referendum yes vote and, in late February, President Rev Sharon Hollis and Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress Interim National Chair Rev Mark Kickett launched the #Yes23 campaign.

“This is an historic opportunity for Australia to acknowledge and honour First Nations people and their deep spiritual ties to this land and to walk together as a nation toward a better future,” Sharon says.

“We support the yes vote for the voice as a pivotal step toward the full implementation of the Uluru statement, so that as a nation we can finally confront the truth of our past and present and make way for justice.”

Mark says now is the time for Australians to unite in support of justice for First Peoples.

“The Uluru statement is an invitation given by First Nations people to the people of Australia,” he says.

“A constitutionally enshrined voice will shape and guide the relationship between First and Second peoples in this country by enabling our people to have a say in the decisions that impact our communities.

“In the same way the 1967 referendum brought Australians together, this is an opportunity for all of us to unite in a big way as we seek to restore justice and promote healing for First Nations people in this land.”

As the discussion around a voice has continued, two indigenous Australians with strong ties to the UAICC and the fight for recognition for their people have watched on with great interest.

Uncle Vince Ross is a retired Victorian Uniting Church Minister, former UAICC chairperson, founder of the Narana Aboriginal Cultural Centre in Geelong and, in 2006, was named NAIDOC’s Aboriginal Elder of the Year.

Alison Overeem runs Leprena, the home of the UAICC in Tasmania, is a former member of the Tasmanian Women’s Council, and in 2019 was added to the Tasmanian Honour Roll of Women for services to the community, education and training, and cultural heritage.

It’s now time to listen properly to the indigenous voice, says Uncle Vince Ross.

They are, indeed, perfectly placed to offer their thoughts on a voice to parliament and what it might mean as part of a broader discussion about ongoing recognition for our First Nations people.

But, more than that, they have much to tell, and teach, us about what is expected from non-indigenous Australians, and if that means offering a few home truths along the way, so be it.

Vince says a yes vote in a referendum would send a signal to First Nations people that at long last they are being heard when it matters on issues that affect them.

“I guess for many Aboriginal people we struggle to convince government that the only voice we hear loud and strong is theirs and it’s now time for our mob to be heard,” he says.

“Any partnership across communities comes about when people decide to make their voices heard and so here we want people to give us that voice in government.

“What I believe can come out of this yes vote for the voice is that government and community will realise we have a voice and want to be heard.

“Strong relationships will be developed and strengthened and there will be further understanding of the true history of this country.

“Our mob will be able to assist in the locking in of policies that actually work and self-determination and self-management will become a reality.

“A voice will push aside those who think the Aboriginal mob don’t know how to do it, and open new doors of opportunities.”

Alison says an indigenous voice in our Constitution is a must, but there is a caveat: it needs to be part of a much wider conversation around justice, truth telling and a treaty.

“I speak into this space as part of the UAICC, as a proud palawa woman, and as a big part of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community, and I think it is a missed opportunity if we don’t have a voice,” Alison says.

“But it’s also a missed opportunity if we don’t embed that in justice, truth telling and treaty.

“Is constitutional recognition on its own going to close the gap for First Peoples across the lands now called Australia?

“Absolutely not, but I think if we don’t start the conversations we might miss an opportunity that may never come again.

“I really don’t want it to be just a voice to parliament, I want it to be voices and, as a collective, that’s how we should speak into the space.

“This is a chance for education to be the healer.”

Like Alison, Vince says a treaty would continue a journey towards self-determination for his people.

“There have been many written and spoken words about welcome and acknowledgement of country, reconciliation, the voice to parliament, black deaths in custody, juvenile detention, domestic violence and other issues,” he says.

“Government has for years struggled with these issues and tried many things but continues to fail.

“The answer lies within the Aboriginal people, if given the mandate through a treaty and not just a voice to parliament but a new structure that brings with it a self-determination model that sustained our communities for thousands of years.

“Aboriginal people have had to learn the Wadjala (white) man way and what is required is trust and for the wider community to understand the Aboriginal way of doing things.

“In a number of communities we see positive action taking place as people from both sides take the time to allow for that cross flow of information.

“This way of doing things is not rocket science, but what mainstream Australia needs to do is to value a culture that’s had a long go at developing lifelong skills and survived.”

Truth telling will form an important part of the move towards a voice and reconciliation, says Alison Overeem.

In 1988, Prime Minister Bob Hawke made a political commitment at Barunga in the Northern Territory to a treaty as part of the journey towards reconciliation.

Just four years later, Prime Minister Paul Keating delivered his famous Redfern speech and, in the process, accepted responsibility for Aboriginal loss, devastation and trauma.

Yet over 30 years later, indigenous Australians can rightly say there has been little movement towards the actions that would cement their rightful standing in a land they have occupied for 60,000 years.

Alison says with reconciliation must come the process of truth telling?

“Let’s relook at that word ‘reconciliation’, because reconciliation assumes that there was something to reconcile in the first place,” she says.

“It also assumes that there was a relationship and I think we have overused the term ‘reconciliation’ more as a comfort to non-indigenous Australians than as justice leverage for First Peoples.

“I think we need to embed it in truth telling, in learning and unlearning.

“Just because you have a reconciliation action plan sitting on your table doesn’t mean you know about us, so we need to reconcile with our own truth telling that sits with us within our education system and our family histories.

“I think non-indigenous Australians need to delve into that first and actually ask the question ‘what are we reconciling?’

“For me, reconciliation is achievable, but we need to use the language that is used around self-determination, not just reconciliation.”

A recent trip to Alice Springs made Alison a firm believer that change will come through our younger generations.

“I think there’s a lot of goodwill out there, and in Alice Springs I was absolutely overwhelmed at the young people and their real passion to want to learn and know more about First Peoples history,” she says.

“But I think the education system continues to let us down and, to quote my mentor, First Nations human rights advocate Cindy Blackstock, ‘today’s learners are tomorrow’s educators’.

“So until we have that three-generational change, I don’t think we’ll get where we need to, but I think we can get there if we keep the momentum going and we make it about culture and truth telling, rather than phrases like ‘reconciliation’.”

Vince admits to being a glass half full type of person and, with that in mind, believes Australians are big enough and mature enough to vote yes to an indigenous voice in our Constitution.

But even if a no vote was to prevail, he believes not all will be lost.

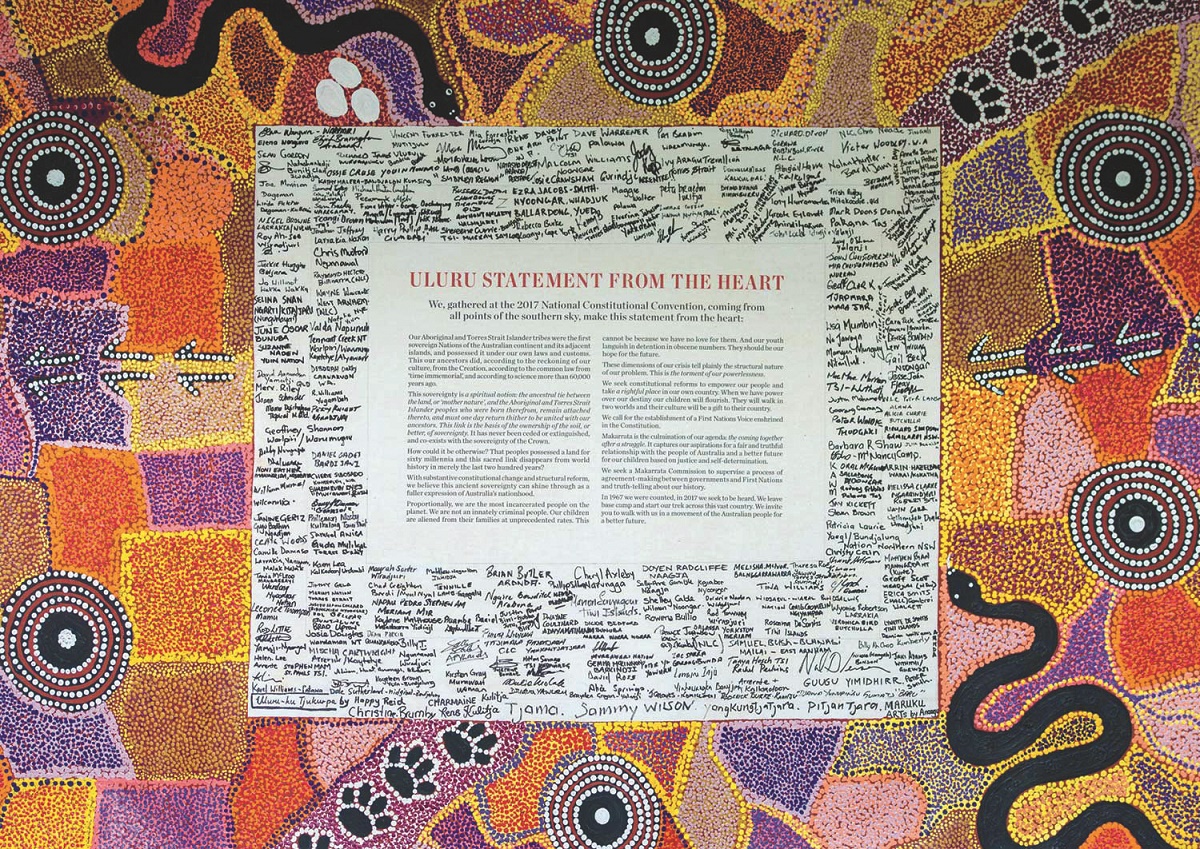

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was the first step towards an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

“It is my belief that even if the vote doesn’t get through we, as a nation, will be further down the track in having a greater understanding of our history that will bring us closer together,” Vince says.

“No way will our voice be silenced any more and the voice will become the foundation for our communities.

“It’s encouraging to see the public response and the opportunity to build that which is required for the mob.

“One of my favourite responses is, ‘together we build’.”

Alison, too, believes there are enough non-indigenous Australians wanting to create real change in the relationship with First Nations people.

“I have actually been quite surprised and comforted by the amount of non-indigenous Australians that want to walk with us, particularly young non-indigenous Australians in the Uniting Church,” she says.

“I think we do have a long way to go but I have a long time to give to it.

“I am still as passionate about this as I was when I was a mouthy little five-year-old.”

And with a voice in place, says Alison, must come the process of healing.

“If there is healing in the voice, and if there is change in people’s thinking, perception and a real acknowledgment that a white Australia has a black history, this is the opportunity,” she says.

“But it’s not just an opportunity for non-indigenous Australians just to say, ‘oh, I’ve done something’,

“I was quoted the other day posing the question, ‘what happens the day after the referendum?’

“And I think that’s a significant question, what does happen afterwards?

“How do we keep Aboriginal voices at the forefront, not just in the back stalls.”

Vince has seen much in his long life and now sees in front of him a country with an opportunity to make a meaningful statement on behalf of its First Nations people.

He feels confident it’s an opportunity enough Australians will want to grasp when they come to tick a “yes” or “no” box at the referendum later this year.

“The word reconciliation speaks about a coming together and discovering our true history and having that capacity to be change agents throughout the wider community,” he says.

“My view is that we as a nation are moving toward a better understanding and that’s where we need to focus on and continue over whatever time it takes.

“Our mob will continue to believe and demonstrate that ability to be able to hang in there and certainly won’t be going away.

“We still have a long way to go but I do believe that if we continue the dialogue then the positives will come out of that, I’m sure.”

And as the clock counts down towards a decision on an indigenous voice in our country’s Constitution,

Alison has one final message for non-indigenous Australians.

“I’d tell them to sit, learn, listen and hear the stories of our old people, that’s who I’m guided by,” she says.

“I’m not the storyteller, I’m the carrier of the story, so we need to dig deep into the storylines and songlines of the elders.

“I would want to ask what they don’t know and what they do know, then work from there because that’s how we learn.”

“A First Nations Voice enshrined in our Constitution offers the chance to … build a more just and compassionate way of being with each other in ways led by First Peoples,” says President Rev Sharon Hollis.

The truth hurts

By Rev Sharon Hollis, Uniting Church in Australia Assembly President

At a recent press conference Professor Marcia Langton said, ‘the truth burns’.

In that simple statement I heard a description of the work of the Holy Spirit who burns the truth into our lives, both our lives as a nation and as a Church.

The Holy Spirit has burnt the truth into my heart and mind and life as I have read and listened to the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart.

I try to make time most days to either read or listen to the Statement. I listen to it in English and I listen to it in First Nations languages.

As I read and listen, the Holy Spirit burns the truth into my heart, into my mind and into my gut.

It burns the truth that sovereignty has never been ceded and can’t be wiped out by colonisation.

It witnesses to the truth that their children are removed in too great a number and their people are disproportionally incarcerated. Not because they don’t love their children or are innately criminal, but because the system is unjust and cruel.

A First Nations Voice enshrined in our Constitution offers the chance to put a spoke in the wheel of this system and help us all build a more just and compassionate way of being with each other in ways led by First Peoples.

As I knelt before Rev Mark Kickett, Interim Chair of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress at the reconvened Assembly, I led the confession of sin on behalf of the Assembly.

We acknowledged our actions have not matched our commitment in the Covenant or the vision of the Preamble.

The truth of this is burnt into my life. I know that, just as Australia must learn to listen to its First Peoples, the Church must also learn to listen to Congress as they struggle for self-determination to lead and guide ministry with First Peoples.

So I will go to the ballot box when the day for the Referendum comes and I will vote Yes.

I will vote Yes to a First Nations Voice with the pain, the hope, the joy and the grace of the Uluru Statement ringing in my ears, the long struggle of First Peoples for self-determination lodged in my heart and a longing in my gut for a better, more truthful way to be in these lands.

And I will leave the ballot box resolved to continue to be part of the work of justice-seeking, for even as we work for a Yes vote, after we have cast our vote, there remains hard, good, holy work of truth-telling and treaty-making to do.

There is also hard, good, holy work to do in the Church to bring about the vision of Congress to be self-determining in all ministry and advocacy for First Peoples in the Church.

I will vote for a Voice and I will remain committed to this work so that I might join in the reconciling work of Christ, which calls us to truth-telling and justice-making and which has the power to make all things new.

“The referendum is a profound opportunity for all Australians to respond to the invitation from Uluru,” says Moderator David Fotheringham.

It’s time to speak up

By Rev David Fotheringham, Moderator Synod of Victoria and Tasmania

Recognising the First Peoples of Australia by the establishment of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice is something that the Uniting Church is proud to support.

I’ve been following the conversation closely since the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in 2017, and I deeply respect and appreciate my colleagues and friends in the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress, in their walking together with the Uniting Church.

I’m very glad to support the YES campaign, and to encourage individuals, congregations and institutions of the Church to take this opportunity to respond to the expressed hopes of First Peoples and deepen our walking together.

God created and sustained this land and the First Peoples long before colonisation.

Dispossession, violence and injustice caused massive damage to First Nations people, their knowledge and their relationships, diminishing the integrity of the gospel proclaimed by the churches.

I am glad that thanks to the work of visionaries like Charles Harris, the UAICC invited the Uniting Church into a covenantal relationship in which “we may all see a destiny together, praying and working together for a fuller expression of our reconciliation in Jesus Christ”.

In 2021, the UAICC Interim National Chairperson, along with the Uniting Church Assembly President, urged the Federal Government to adopt the proposal for a constitutionally enshrined national Voice, recognising that such a Voice would be fed by local and regional representation, and being clear that a voice which was not given recognition in the Constitution would miss the primary appeal of the Statement from the Heart.

The Statement from the Heart came out of a thorough process of First Peoples-led dialogue, culminating in the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru.

It clearly calls for a constitutionally enshrined Voice, as well as a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making and truth-telling.

I’m glad that around the Church there have been many opportunities to unpack this rich and moving statement.

Having heard from the UAICC and the Statement from the Heart, the Uniting Church’s Assembly Standing Committee has strongly affirmed the Church’s support for the Voice, as a step towards Voice, truth-telling and treaty.

The referendum is a profound opportunity for all Australians to respond to the invitation from Uluru.

It is a means for First Peoples to be recognised and heard on matters that have direct effect, in a way that national consultation among First Peoples’ has requested, allowing for details of structure and process to be overseen by the Parliament.

I’ve been encouraged at both ecumenical and interfaith forums to consistently find strong support for the Voice.

Along with colleagues and friends from the UAICC, I am keen to urge strong and clear support for the Voice. I encourage respectful conversations around all aspects of addressing injustice for First Nations people, and I pray that through this we will respond to our high calling in Christ to be instruments of reconciliation and peace: Following Christ, walking together as First and Second Peoples seeking community, compassion and justice for all creation.

“For me, the Statement from the Heart, and the Albanese Government’s commitment to getting the work done, gives me hope,” says NSW/ACT Synod’s Director of First Peoples Strategy and Engagement, Nathan Tyson.

Call for change rings clear

When Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress members met in Darwin for their national conference recently, discussion about the Voice to Parliament was high on the agenda.

And in that discussion lay two questions.

When most referendums since 1901 have ended in failure, what hope can our First Nations people place in this one?

Can the 1967 Referendum, when over 90 per cent of Australians voted yes, give hope that the Voice to Parliament will be accepted by the Australian people?

The 1967 Referendum gave First Nations people the right to be counted in the Census and the opportunity to vote.

The Referendum on a Voice to Parliament gives the people of Australia a chance to allow First Nations people not only to be seen and counted, but to be listened to so that they have constitutional recognition and a constitutionally enshrined First Nations voice.

For our First Nations people, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

That mood of an urgent need for change was summed up in a speech to UAICC members at the national conference by Nathan Tyson, the NSW/ACT Synod’s Director of First Peoples Strategy and Engagement.

In his speech, Nathan captured what was at the heart of the case for a yes vote later this year.

“The Voice is a tangible action that can make a real difference in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples and communities,” Nathan told the national conference.

“If Christians accept that the teachings of Jesus guide us in the way we are to live and act, it is clear that there is a theological imperative for Christians to stand in solidarity with First Peoples seeking justice, and to support the Statement from the Heart and its outcomes of Voice, Treaty and Truth.

“For me, the Statement from the Heart, and the Albanese Government’s commitment to getting the work done, gives me hope.

“I have not felt such hope since the Redfern speech by Paul Keating.

“But this is more than a speech. The Voice is tangible action that can make a real difference to the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities.

“As a Christian I believe hope is important, so I hope that justice will be done.”

Joining Nathan at a question and answer session during the national conference was distinguished academic Anne Pattel-Gray, Head of the School of Indigenous Studies at the University of Divinity.

“We’ve gone so long being unrecognised, unheard, and made outcasts in our own country,” Anne says.

“It is time that we moved from the periphery to the centre.

“It is time that we’re seen and heard.”

UAICC Interim National Chair, Rev Mark Kickett, says that now is the time for Australians to unite in support of justice for First Peoples.

Mark says the Covenant in the Uniting Church ties First and Second Peoples together in a binding way so that together we are able to contribute to a more just Church and nation.

“Now is the time for us to hear the call of God to seek justice by doing what is right for our nation”, he says.

“Like Jesus, we are called to be bearers of justice, not just in our words, but in our actions and by changing systems which continue to deny the place and rights of the First Australians.”

The UAICC encourages churches, communities and individuals to inform themselves about the Uluru Statement and what it asks of our nation, and to create respectful spaces for yarning about the impact a First Nations Voice will have.